KEEPING ORDER ON THE FRONTIER

Published 5:00 pm Tuesday, September 25, 2007

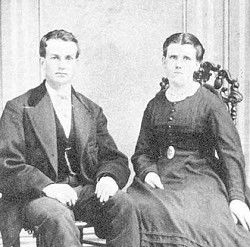

- <I>Contributed photo</I><BR>M.P. Berry and his second wife, Jane Eddon Berry, are shown in this photo provided by Kathy Milner of Portland, whose grandmother was Jane's sister.

Montgomery Berry was the first Sheriff of Grant County in 1862, the second superintendent of Oregon State Penitentiary in 1866, and the first Territorial Customs Agent of Sitka, Alaska in 1874.

Major Montgomery P. Berry was born in Kentucky in 1827. His military career began in Ft. Levenworth, Kansas territory. He served in the Mexican War and received his title of major after raising three companies of federal troops during the civil campaign.

He and his wife Sara Isabella immigrated to Oregon in 1861 and lived in Wasco County. When Wasco County was created on Jan. 11, 1854, it consisted of all of Oregon Territory between the Cascade Range and the Rocky Mountains and from the California border to the Washington border. This was the largest county ever formed in the United States.

Major Berry was a good friend of George L. Woods, a Wasco County judge at the time Grant County was formed from Wasco County. Berry was elected the first Sheriff of Grant County and served in that position in John Day from 1862 to 1866.

He was appointed as superintendent of Oregon State Penitentiary on Sept. 14, 1866 by George L. Woods, two days after Woods was elected governor. Berry and his wife Sara Isabella settled into the Salem community taking part in various community activities. Sara Isabella was a friend of Louisa Woods, wife of the governor and the two women took music lessons together at Sacred Heart Academy in Salem.

Berry was appointed to manage the penitentiary and to instill military efficiency and discipline in the prison. He brought with him Lt. Gale from the Oregon Infantry. In an Oregon State Penitentiary employee newsletter, The Gladiator, dated Nov. 3, 1955, Sgt. Joe Johnson, a history buff, provides a description of what his research revealed Berry’s life was like at Oregon State Penitentiary:

“The man astride the mount held his reins in one hand and his hat with the other and he leaned forward in the saddle with his head bowed to protect his face from the fury of the windswept rain that cascaded down from the sullen sky. He kept the bay horse at a gallop as he splashed heedlessly through the sprawling puddles of East State Street in Salem. Under his breath he muttered words to the effect that it was damn unnecessary to locate the prison so far from town.

“When he finally brought the panting steed to a halt in front of a drab little building identified by a weathered inscription, Superintendent’s Office – Oregon State Penitentiary, he dismounted and tethered the animal to a post and hurriedly entered the building. Once inside, he doffed his drenched hat with an appropriate comment about the weather and addressed the stern, austere looking gentleman behind the desk: ‘Mr. Berry, I’m afraid I have bad news for you.’

“The man behind the desk was Superintendent Major M. P. Berry and the calendar on the wall behind him showed the date to be Wednesday, Jan. 10, 1867. He looked up at the lieutenant for a petulant instant and then back to the menu he was preparing.

“‘Well, Lieutenant?’ His tone was crisp, nearly acid.

“‘Farmer Smith said that he can not spare beef at this time, sir.’ The officer spoke regretfully as though it was something personal. ‘I tried to bargain with several other farmers in the vicinity and as far north as Gervais, but they are all reluctant to part with their meat at this time of the year.’

“Minutes of silence ensued, interrupted only by the rain beating on the roof and the annoying rattle of something clattering against the building outside.

“‘I guess this will have to suffice,’ he said, more to himself than for the benefit of the lieutenant who still stood patiently waiting for further orders. He proceeded to read aloud: ‘6:30 A.M. breakfast: bacon, beans, coffee and bread. Weekday dinners: coffee, bread, and potatoes.’ After potatoes he had written fresh beef. He scratched it out. ‘Sunday dinner: rice, syrup, and coffee.’

“He placed the menu on the desk and removed his glasses as he stood up and strode slowly across the room to the stained glass window that overlooked the prison yard. The lieutenant was beside him.

“‘It’s a mess alright, sir. I don’t blame you for being disgusted.’

“They surveyed the barnlike building that housed the prisoners and the dilapidated fence that stretched to the gully and ended.

” ‘I guess I should be philosophical about these problems that continually confront me, Lieutenant, but sometimes it seems like a hopeless cause. Providing adequate food to sustain the prisoners is one thing and security is another. That fence is a laughing stock. I’ve appealed to Governor Wood again and again for funds to complete it.’

” ‘The legislators will be meeting again next week sir. Wouldn’t the Governor permit you to speak to them yourself and explain the urgency of funds to improve the security of the institution?’

” ‘Lieutenant,’ his voice seemed to have lost its metallic incisiveness and instead took on the soft quality of a seer prophesying the future. “Some day the State of Oregon may have to deal with not 50 or 60 prisoners, but maybe five hundred or even a thousand. I wonder what security they will have developed then. Maybe in 1950 or 1960 the administration will look back and laugh at my problems and our prison of wood buildings and a 14-foot-high fence.'”

The task of managing the Oregon State Penitentiary was a challenge for Major Berry as reflected in his report to the governor Sept. 1, 1868. He says, “At the time of entering upon the duty assigned to me, it was a totally new field of labor, and one which I had never contemplated, excepting, as other citizens from a distance; and when brought into immediate contact therewith, realized that fine spun theories upon the control of convicts and the utilizing of their labor sufficiently to make them pay the annual expenditures made on their behalf, was one branch of the subject, and the actual proceeding was another.”

His concern for untrained staff working as guards in this new prison caused him to comment, “The continual strain upon their vigilance either wears them out, so much that they retire voluntarily, or they become careless and have to be removed.”

He introduced a supernumerary system where officers were placed on half salaries while they learned the business, their promotion assured upon a vacancy occurring in the regular line.

Regarding underclothing for prisoners he stated that underclothing is unknown in this prison, unless ordered by the physician for isolated cases. In nearly all other prisons from which reports have been received regular returns of underclothing are made. He proposed that some good strong cloth be introduced for underclothing.

He recommended changes in the use of inmates as kitchen help for officers mess. He thought it endangered the officers. He wanted a building constructed for living quarters for officers with a mess house erected therein where they would cook their own food. Berry’s other changes included increasing the night patrol, using vacant cells in the lower tier as hospital beds as no hospital area was built in the original plans. He provided an area where school was taught by better educated fellow inmates.

He lamented that many men discharged from prison had no clothes to wear out due to the wilful neglect by staff of caring for inmate property. He furnished clothing for them.

His recommendations on discipline are as follows:

Punishment for violation of institution rules:

First offense: Lecture from supervisory officer

Second offense: Reported to superintendent to admonish the culprit.

Third offense: Carries a shackle, if he already has one a second one is placed on the first one.

Fourth offense: Reported to the superintendent who in most cases gives offender a sanction of bread and water from 1 to 10 days in solitary.

Flogging was used as a last resort and then only when the prisoner breached every rule of discipline or committed an outrage upon a fellow prisoner of such nature that he places himself outside the pale of mercy.

Mr. Berry himself suffered sad personal losses with the death of his infant son, March 24, 1868. The Salem Unionist newspaper of the 26th reports that Major Berry and his wife Sara Isabella, brought the remains of their infant son by boat to The Dalles where a funeral service took place. A Wasco County newspaper of September 17, 1870 reports the funeral of Sara Isabella, wife

of Major M.P. Berry. Mrs. Berry had been an invalid for a period of two years as reported in her obituary. Her body was laid to rest in the St. Patrick Catholic Cemetery. Mrs. Berry died three days after Major Berry’s term of office as Superintendent of Oregon State Penitentiary concluded.

Major Berry was appointed as an Indian Agent at Fort Hall, Idaho after he left Oregon. “In his annual report for 1871, Fort Hall agent Montgomery Berry alluded to “difficulties between certain white men who have occupied a portion of those prairies and the Indians from this reserve who were out on the annual camas-gathering expedition.”

Unspecified “difficulties” were not the only sign of Shoshone-Bannock displeasure with the government’s failure to protect their rights. Tay-to-ba and A-wite-etse, two Bannock headmen and signatories of the Fort Bridger treaty, reminded their agent that the prairie was reserved for them by the Fort Bridger treaty. Berry agreed with their interpretation but also suggested that certain settlers were using the misspelling in the treaty in an attempt to deny Indian claims.”

In the June 8, 1870 U. S. Census for Salem, Oregon , Jane Eddon age 17, is a housekeeper in the home of Montgomery Berry age 42 and Sarah Isabella Berry age 34, on Cottage Street between Court and Chemeketa Street in Salem. After

the death of Sarah Isabella Berry, Jane Eddon would wed Montgomery Berry. Oregon court records reflect the marriage of Major M.P. Berry to Jane Eddon in Portland November 14, 1872. Jane Eddon was born in England and came to

Oregon with her parents John and Elizabeth Cross Eddon, sisters Annie and Mary. Berry and Eddon had one son Montgomery P. Berry, Jr., born in 1874 in Salem, Oregon.

March 16, 1874, Berry was appointed by President U.S. Grant as Collector of U.S. Customs in Sitka, Alaska. Jane Eddon Berry apparently remained in Oregon caring for their son while Montgomery Berry was working in Sitka, Alaska. In the 1880 U.S. Census for Turner, Oregon their son is listed as a boarder in the household of Jane Eddon Berry’s sister, Annie David. Jane may

have visited Sitka from time to time before her death in Oregon in 1896.

“Duty Station Northwest” by Lyman L. Woodman, Lt. Colonel, USAF Retired, Alaska Historical Society reports:”In 1877 the U.S. Government transferred the government buildings in Sitka to Collector M. P. Berry. The ship

carrying the military left Sitka at 6:00 P.M., and according to a local Creole the settlement then went wild.” He wrote in his diary, “this evening the former quarters of the officers and soldiers, as well as all the government warehouses, were robbed and plundered. The citizens succeeded in expelling the Koloshes from the city but for how long?”

“Collector Berry submitted a gloomy report to Secretary Sherman on Sitka conditions. He said that immediately upon the troops departure the Indians had, “assumed an arrogant bearing, and plainly informed us that there was neither gunboat nor soldier, therefore they had no fear. Before the steamer left the dock. Russians and Indians began to raid the government buildings. They have completely gutted the hospital.They are removing the government stockade, and have also commenced to destroy the blockhouses. The Indians indulged in threats which no doubt they will put in practice when they find that no gunboat of any kind appears on the scene.”

Berry weathered this storm and in 1880, he ran for delegate from that district for congress but was not elected. Colonel Mottrom D. Ball was elected. Berry appears to have taken up the study of law after his move to Sitka, Alaska. He remained in Sitka where he advertised in The Alaskan Newspaper as “M. P. Berry, Attorney at Law, Sitka, Alaska.” He is listed as an attorney representing Sah-quah, an Indian slave who was fighting for his freedom since Alaska had been purchased by the United States and slavery was illegal in the U.S.

Berry was a well loved and respected citizen of Sitka at the time of his death December 18, 1898. He is buried in the Sitka National Cemetery. His second wife, Jane Eddon Berry, died June 29, 1896 and is buried with her father John Eddon in the Hobson Whitney Cemetery near Sublimity, Oregon.

Their son, Montgomery Berry, Jr. worked for several years at the Oregon State Reform School on Turner Road (now Mill Creek Correctional Facility) where he was a cook. His wife Winnie Silvers Berry served as a seamstress there. He died in a tragic accident when he contracted blood poisoning while camping at Diamond Lake in 1900. He is buried in Twin Oaks Cemetery in Turner, Oregon. Winnie remarried to Theodore C. Parker, September 25, 1901. She died July 18, 1941.

Sue Woodford Beals is an author and historian. This article comes from her research on the superintendents of the Oregon state prison system.