School nurses play vital role in taking the temperature of COVID-19

Published 5:00 am Friday, September 18, 2020

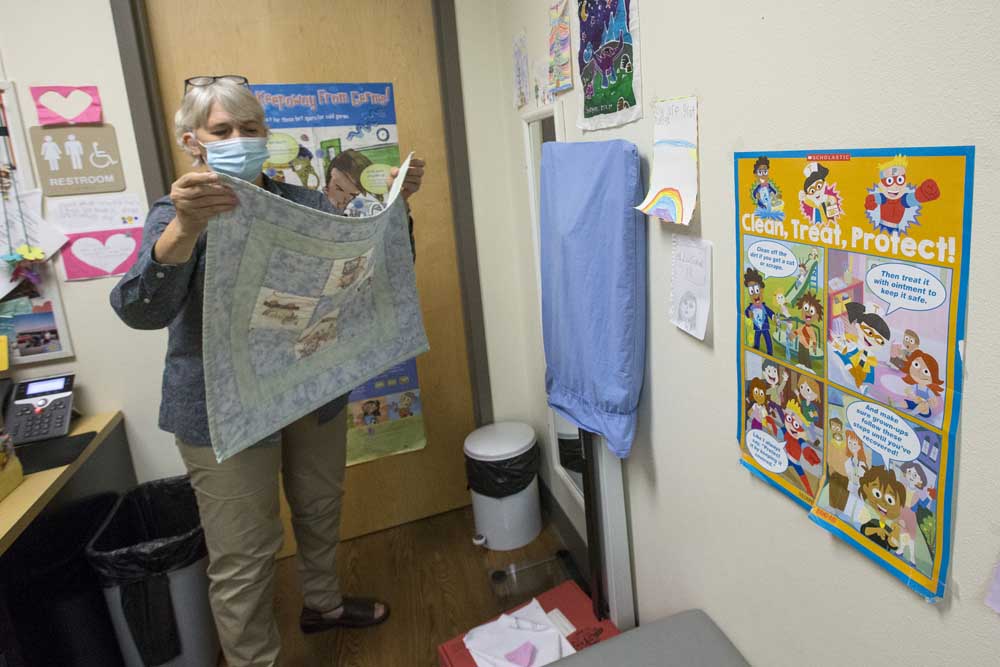

- Kim Kirk, a nurse at Tom McCall Elementary School in Redmond, works on removing the items from the walls of her office on Wednesday, Aug. 12, 2020. Kirk said she was taking everything down as a precaution with the COVID-19 virus.

Neither a COVID-19 pandemic nor an outbreak of head lice will keep school nurses from manning the front lines of maintaining school health.

Trending

They’ll be the ones donning masks, gowns and gloves and leaning in to help students come back to school for in-person learning once communities meet the state-required low virus numbers.

While many Oregon schools won’t be opening their doors to students until November, school nurses will stand strong alongside of school administrators planning how to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

“COVID-19 has changed our landscape so significantly,” said Kim Kirk, a school nurse for Redmond School District. “While we’re starting off the year with distance learning, we’ll miss seeing our kids in person.”

Trending

Although schools have been closed to students since March, school nurses have been suited up to handle the outbreak from planning how to manage the health and safety of students and staff for in-person instruction, to ensuring that students with special health needs still get the services they need.

Oregon’s nurses are armed and prepared with personal protective equipment, rules to measure physical distancing, health screenings for students and staff with symptoms, setting up isolation rooms and sanitizing protocols, said Corinna Brower, a registered nurse and Oregon Health Authority state school nurse consultant at Adolescent and School Health Programs.

While they may not have to go as far as taking every student’s temperature upon arrival, school nurses understand the rules of education and health and often provide the bridge between the two.

“This is not the first outbreak we’ve ever dealt with,” Brower said. “This is something we’re used to doing.”

As school districts grapple with how best to open or a combination of in-person and online learning, depending on its size and population, the school nurse needs to be in on those conversations, said Wendy Niskanen, past president of the Oregon School Nurses Association and school nurse at Klamath County School District.

“The school nurse is an expert in understanding the health language and the education speak,” Niskanen said. “Educators need us right now.”

In order for K-12 schools to open, they must meet COVID-19 testing metrics outlined by Gov. Kate Brown in July. Some schools will be able to open with online classes, others will start with some days of in-class learning and the rest distance learning. Others will open for kindergarten through third-grade.

The reopening school guidelines require the entire state to have weekly positivity rates of less than 5% for three weeks. In order for schools to reopen, the county where the school is located must have 10 or fewer cases per 100,000 people over a seven-day span for three consecutive weeks. Some counties can meet those benchmarks, but not the state as a whole.

“The key is to get to a place where the coronavirus in the community can be surrounded and kept down,” said Pat Allen, Oregon Health Authority director. “We’re making good steady progress.”

Around 580,000 students are enrolled in Oregon schools. Experts have said students need classroom time.

“The school nurse needs to be right there with the principal,” Niskanen said. “This way the school is assured to meet the guidance and interpret it appropriately.”

Each of the 340 school nurses statewide needs to develop a set of guidelines that is organic to the school campus, Niskanen said.

“Schools are communities and every school is different,” said Linda Mendonca, National Association of School Nurses president-elect. “The goal is to get back to in-person learning, but we have to make sure that students, families and staff feel confident.”

Nurses are spread thin

In Oregon, there are 340 school nurses, that includes registered nurses and licensed practical nurses. The state recommended ratio is 1 RN to every 750 students in a general school population. The statewide average is 1 RN for every 2,353 students, according to the 2019 Report Nursing Services in Oregon Public Schools. Oregon’s nurse-to-student ratio, when you include mandates for higher-needs students, is 1 RN for every 5,565 students.

Nationwide, a quarter of the schools don’t have a school nurse. Here, in Oregon, school nurses serve up to five schools and a quarter of them have six or more schools in a region, Brower said.

Only 10% of the school nurses in Oregon work at a single school.

In Oregon, there are gaps in service and for rural communities, it is a challenge to get skilled nurses, Niskanen said. Ideally, every school should have a dedicated school nurse, Brower said.

“There’s strong evidence that having a school nurse in every building has an impact not only on health but educational outcomes,” Brower said. “Nursing supports the needs of students.”

COVID-19 roles

While the schools have been closed, school nurses are still working. They have been creating school health protocols and policies, supporting student physical and mental health, staff training for medication tasks, health screenings, health education and continuing nursing education and re-entry planning, Kirk said.

School districts are looking at the metrics outlined by Oregon’s governor and trying to find a path to in-person learning. In addition, parents will need to be trained on how best to assess their children’s health as the health guidance has changed.

Everyone involved with in-person learning will need to be trained to eyeball students health. Starting with the school bus drivers, students’ health will be assessed and if a child looks lethargic or has a fever of 100.4 degrees or above, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing and a cough, they’ll be sent home.

On campus, school nurses have been creating isolation areas for students who may display COVID-19 symptoms. They’re establishing protocols for sanitizing the space. At the same time, they’re realizing that they won’t be able to hand out snacks and be that emotional touchpoint for students.

“I’d often give out snacks and chat with students,” Kirk said. “That will have to stop for this year at least. That will be different. That’s sad to me not to be able to provide emotional support.”

Students most likely will make an appointment to see a school nurse who will log in the comings and goings of students to be used in case contact tracing is required if an outbreak occurs, Kirk said.

“It adds a layer of heightened intensity for our jobs,” said Kirk. “Our primary job is to keep ourselves safe and our children safe. “

Schools discuss plans

In counties with fewer than 30,000 residents, schools with 250 students or fewer can reopen if there are no more than 30 new COVID-19 cases in the county for three weeks. The local public health authority also must find that there is no community spread of COVID-19 in the school’s attendance area.

In Crook County there are two schools, Paulina School and Brothers School, each has fewer than 20 students and can have in-person instruction.

In Pendleton, the district is working toward in-person learning, said Superintendent Chris Fritsch. The district doesn’t have a full-time nurse assigned and contracts nursing through the InterMountain Education Service District, which serves school districts in Morrow, Umatilla, Union and Baker counties.

“They will be plenty busy as a consultant to staff and parents as well as monitoring the day to day health services in our buildings,” Fritsch said.

Bend La-Pine School District said its school nurses will be available to provide guidance to families of students needing support services, said Tami Pike, Bend La-Pine Schools Health Services supervisor in an email. Nurses will also reach out to some families of students with more complex medical needs to update health plans in preparation for when students return to school in person.

The governor’s plan

Basing school reopening on health metrics will enable schools to open and stay open. Schools and health officials don’t want benchmarks to be overwhelmed too easily so that a school district will open and then close. That doesn’t help students. Schools are being encouraged to provide in-person education for students in kindergarten through third grade because younger students get the virus at lower rates, get less sick when they get COVID-19, and seem to spread the virus less than older children or adults.

Younger students also need access to in-person instruction to build literacy and numeracy skills critical to their continued learning.

In order to reopen schools, everyone in the community has to help, said Bend pediatrician Dr. Rebecca Hicks.

Hicks and 150 other doctors recently sent Gov. Brown a letter urging her to close bars, gyms and other non-essential businesses to reduce the spread of COVID-19 to enable schools to reopen for in-person classes.

“Kids aren’t going back to school unless stricter controls go forward,” Hicks said. “We agree with the metrics the governor has put forth.

“We’re just not doing enough. We have to get to low levels. We do have a way out of here. We don’t have to wait for an effective vaccine. We just have to follow the roadmap provided by other countries.”

In the interim, schools are planning to start off the year with distanced learning, said Kelly Jenkins, Redmond School District spokeswoman. Six weeks into the fall term, the district will re-evaluate the metrics to determine if they can be met to move forward with in-person instruction.

“We want to give our schools and parents time to plan,” Jenkins said. “We know our parents feel there’s no replacement for in-person instruction,” she said. “The only way to come to that is to maintain distance, wash your hands and wear a mask. The sooner we all do this, the sooner we’ll get back to in-person instruction.”