Partisan plans for redistricting make consensus a long shot

Published 2:45 pm Tuesday, September 7, 2021

- Redistricting puzzle

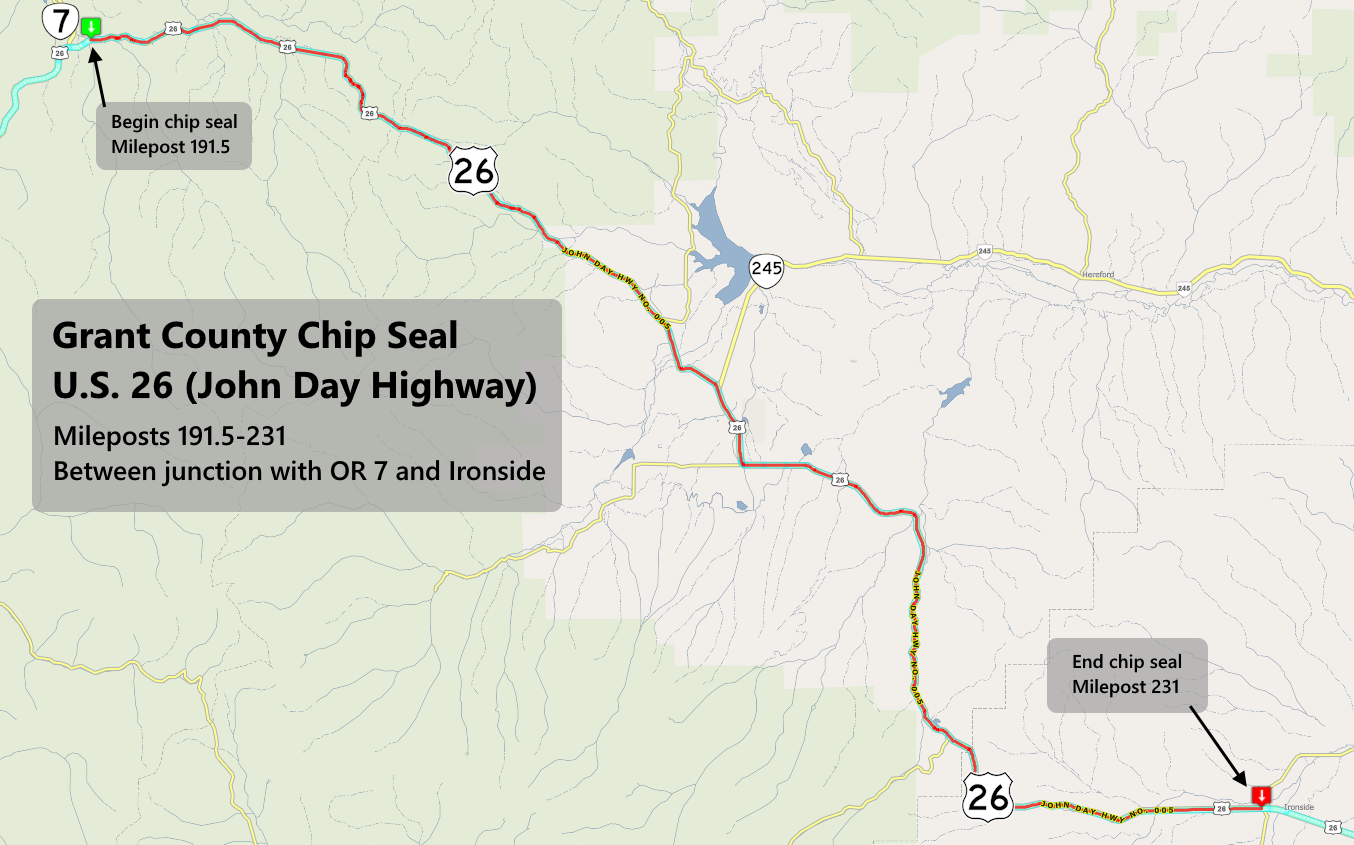

Legislative leaders on Friday released competing plans for new political districts to be used beginning with the 2022 election.

Hopes for a quick consensus to meet a Sept. 27 deadline set by the Oregon Supreme Court for new maps were met with immediate partisan crossfire at a meeting of the House and Senate Redistricting Committee.

Rep. Shelly Boshart Davis, R-Albany, co-chair of the House Redistricting Committee, was less than a minute into the first presentation of the day when she impugned all redistricting in the 21st century.

“Our current districts have diluted the voices of Oregonians for two decades to advance one political party and incumbent politicians,” Borshart Davis said.

Rep. Andrea Salinas, D-Lake Oswego, the committee’s other co-chair, objected to the accusation at the very first public showing of plans required by law to reflect the population changes from the 2020 U.S. Census.

“These maps aren’t final,” Salinas said. “None of them are.”

In all, lawmakers showed eight different maps at the Friday meeting.

Three plans were submitted for the 60-member House — one each from Democrats in each chamber and one from Republicans.

Three plans were put forward for the 30-member Senate. The authorship had the same split as the House plans.

Two plans were displayed for the six congressional districts — one from each party — including Oregon’s first new seat in 40 years.

The maps were released to the public just minutes before the 8 a.m. start of the meeting, which was held online out of concerns over the recent COVID-19 spike in Oregon.

A series of public hearings across the state — dubbed “the road show” — were cancelled and will now be 12 virtual hearings.

While revisions of maps are expected, the first drafts shed some light on the push and pull that will go on if the legislature meets as informally planned on Sept. 20 to vote on a single plan.

Sixth U.S. congressional seat included

An immediate difference was where to put the new, sixth congressional seat — Oregon’s first new congressional seat in 40 years.

Democrats and Republicans both used common redistricting methods known as “cracking and packing.”

The proposed Democratic map “cracked” Portland into chunks parceled out into three districts. The newest of the configurations stretches east from Portland to Hood River then south to Bend.

The cities are in Hood River and Deschutes counties — the only counties east of the Cascades won by President Joe Biden in his defeat of then-President Donald Trump in 2020.

The change would shift the cities out of the district currently represented by congressional delegation’s only Republican, freshman U.S. Rep. Cliff Bentz, R-Ontario.

The incumbent for parts of the Democrats’ proposed new district would likely be U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer, D-Portland, often considered the most liberal of the state’s four current Democrats in Congress.

Under the Democratic plan, Republicans would be “packed” into the remaining areas east of the Cascades, with an extra slice in the southwest pushed through Jackson and into Josephine counties.

The changes would make Bentz’s sprawling district border parts of Washington, Idaho, Nevada and California. It would have the Snake River at its eastern end and be a short drive to the Pacific from its western-most part.

The proposed district from Portland to Bend would be less Democratic leaning than Blumenauer’s current constituency, but would remain a tough race for Republicans to win.

The other four districts would be remolded to make them less of a nail biter for Democratic incumbents, especially U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Springfield, and U.S. Rep. Kurt Schrader, D-Salem.

Portland-centric

Republicans proposed congressional maps start by “packing” as many Democrats as possible into a district covering most of Portland.

A GOP win in Oregon’s largest city would become even more of a long shot than today.

But the tradeoff is the GOP plan continues to isolate Bend and Hood River as Democratic “blue” islands in a Republican “red” sea of voters in Bentz’s district.

The Republican plan would give each party a likely slam dunk win: Democrats in Portland, Republicans east of the Cascades.

But the other four districts would be configured in a way to make a Republican win range from possible to probable.

Big Bend changes

Much of the focus Friday was on the congressional maps with a new district shoehorned within an Oregon map currently holding five.

But big changes for Senate and House districts were put on the table as well.

Three separate plans were submitted for legislative districts — one each from House Democrats, House Republicans and Senate Democrats.

Drawing those lines was already tough because of the requirement that each Senate seat encompass two House seats — called “nesting.”

State law also states maps should strive to have nearly equal populations in districts, follow major geographical landmarks such as mountains and rivers, maintaining loosely defined “communities of interest,” and take into account shared transportation routes.

The federal Voting Rights Act includes prohibitions of intentionally dividing lines that would dilute the voting power of racial minorities.

The area most ripe for redistricting is around Bend, which grew by over 20% in the past 10 years, twice the state rate.

The total number of House seats would increase in the region, with at least two becoming more likely Democratic wins based on voter registration.

House District 54, which Democrat Jason Kropf, D-Bend, flipped after a streak of five Republican wins despite an ever-growing Democratic voter registration, is the Democrat’s toehold east of the Cascades.

Senate District 27, currently held by Sen. Tim Knopp, R-Bend, has the most population of any Senate district. A realignment could move it from being a swing district that Knopp was able to retain in a tight 2020 race to a fate similar to House District 54 as voter numbers favoring Democrats eventually catch up with incumbents from the other party.

Knopp said it was too early to get overly concerned about the final outcome. He pointed to additional plans submitted to the redistricting committees by Oregon residents using a state software program to draw lines.

Lawmakers also have several hearings to get input from all areas of the state and political hues.

“There hasn’t been agreement on the plans,” he said. “There can’t be agreement without the public.”

Governor’s veto looms

The stark differences in starting points makes it harder to get to the finish line. A compromise plan can get through the legislature but still be vetoed by Brown.

The Oregon Constitution calls for redistricting to be done by the legislature and approved by the governor.

But this official “Plan A” has only worked twice since 1911.

Partisan splits in the legislature, vetoes by a governor or legal challenges that threw the maps into the courts have more often been the result of redistricting.

The constitutional fallback is for legislative districts to be drawn by the secretary of state, while maps for the congressional districts are handled by a special panel of five judges. The plans then go to the Oregon Supreme Court for review.

Democrats currently hold a political “trifecta” in Oregon — the House, Senate and governor’s office are all controlled by the party.

It seemed that 2021 would be a rare year to have the process in the Constitution play out with Republicans limited to complaining from the sidelines.

The COVID-19 crisis upended expectations.

U.S. Census data was delayed by six months, and it took an Oregon Supreme Court decision to give the legislature a shot at coming up with maps.

But the court gave lawmakers a compressed timeline. A plan has to be proposed, voted on by the full legislature and approved by Brown before Sept. 27.

After that, the secretary of state and the judges panel would draw the lines, which the court would review.

The pandemic also played a key role in a controversial deal giving Republicans a central role in redistricting.

House GOP leaders used parliamentary tactics to slow the progress of Democratic legislation during the 2021 session.

House Speaker Tina Kotek, D-Portland, worried the constitutionally mandated deadline to end the 180-day session at the end of June would arrive with key bills still stalled without a final vote. Under state law, all legislation dies with adjournment.

Republican role added

Kotek struck a deal with House Minority Leader Christine Drazan, R-Canby. In exchange for speeding up voting on bills, Drazan would get a seat on the House Redistricting Committee. The move gave Republicans equal numbers of the panel.

Drazan essentially has a veto over what plan the committee could send to the legislature.

But Drazan also had to decide how far to push her advantage. Any compromise worked out by lawmakers could still be vetoed by Brown.

That would send legislative redistricting to Secretary of State Shemia Fagan, a former Democratic state senator from Portland elected to the state’s top elections job in 2020.

If that happened, Republican legislators would be shut out of any say in districts that would be in place for a decade.

“It will be a tough needle to thread,” Drazan said during a media call after the meeting.

Sen. Kathleen Taylor, D-Milwaukie, chair of the Senate Redistricting Committee, said arguing over the first maps didn’t account for the public hearings, which could point out problems and ideas the lawmakers missed in making their maps.

“We want to hear what Oregonians have to say about the maps proposed — what works, what doesn’t,” Taylor said in an email.

Change unlikely until 2032

The League of Women Voters and other non-partisan groups hope this will be the last redistricting under the current system.

California, Washington and several other states have moved away from the traditional redistricting process used in Oregon to create independent commissions to draw new district lines.

Across much of the nation it is Democrats championing commissions since more states have have Republican trifectas than Democrats.

Whichever party benefits, reformers say lawmakers need to be removed from the process.

“There is no amount of technical savvy or sophisticated mapping software that removes the inherent conflict of interest that exists when partisan legislators are given the benefit of drawing their own electoral lines — the fox is guarding the henhouse,” said Norman Turrill, chair of People Not Politicians, a Portland-based coalition advocating for a commission in Oregon.

The group still hopes to get a ballot measure before voters in 2022.

But a victory most likely would only mean the legislature would be out of a job drawing maps after the next census in 2030. Candidates won’t run on those maps until 2032.

The deadline for submitting redistricting maps for consideration by the House and Senate redistricting committees has been extended to Sept. 8. For full information and instructions on how to build maps for the legislative and congressional districts can be found at www.oregonlegislature.gov/redistricting

Written testimony on redistricting can be submitted by email at Oregon.Redistricting@Oregonlegislature.gov. To comment by telephone, call 833-588-4500. Mailed comments can be sent to: Oregon LPRO Office, attention: redistricting team, 900 Court Street NW, Room 453, Salem, OR 97301.

“There hasn’t been agreement on the plans,” he said. “There can’t be agreement without the public.”

Sen. Tim Knopp, R-Bend