OHA, DEQ set to monitor 150 public drinking water systems for PFAS

Published 7:00 am Tuesday, November 9, 2021

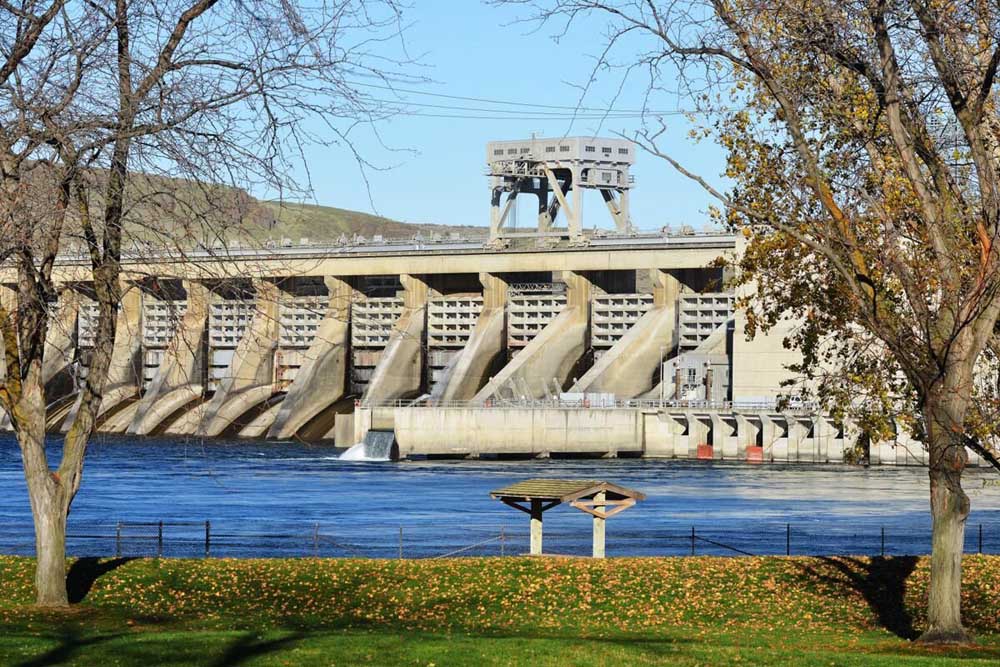

- McNary Dam in Hermiston is among the 150 sites selected by the Oregon DEQ and OHA for water sampling to test for the presence of PFAS contamination

LA GRANDE — The state of Oregon plans to test 150 drinking water systems across the state for the presence of PFAS, or per- and poly-fluorinated substances.

Trending

Of those 150 sites to be tested, 17 reside in Northeastern Oregon, including 11 in Umatilla County, and two in Union County. Baker, Grant, Morrow and Wallowa counties each have one testing site. The locations were chosen due to their proximity to known or suspected PFAS use or contamination sites.

“We took a look at all the small public water systems, and that’s those that serve fewer than 10,00 because the big ones have already been sampled, and we looked at places where there might have been potential — and I’m underlying potential — PFAS sources,” said Harry Esteve, communication manager for the Oregon DEQ. “We overlaid those on the maps of water systems, and selected that list of 150.”

Those testing sites include the cities of Irrigon, Pendleton, Milton-Freewater, Elgin, John Day and Joseph. Other sites include the Ash Grove cement manufacturing site in Baker City, the Amazon data center in Umatilla and the Sacajawea Mobile Home Park in La Grande.

Trending

Results from the first few collection sites should be finished and analyzed by the end of November. Of the 150 sites across the state, only 20 have been sampled so far, according to Esteve.

“Samples from the first 20 public water systems have been collected. We made a list of the 150 we are going to sample eventually, over time, but we started with 20 — and frankly we started because they were kind of near our lab which is in Hillsboro.” Esteve said. “So we can get out there quickly and get some results a little bit more quickly. Travel is still a little bit on the iffy side, given the Delta variant.”

This is not the first time Oregon has tested its water systems for the presence of the chemicals. Between 2013 and 2015, a study from the OHA tested all major public drinking water systems in Oregon cities with more than 10,000 residents and found no detections of PFAS. So far, Oregonians do not seem to be exposed to these chemicals in harmful amounts through their water, according to the Oregon Health Authority.

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, in partnership with the Oregon Health Authority, will be conducting the testing. The 150 sites that will be tested is up from the 65 tested between 2013 and 2015, and now includes smaller rural communities and cities. The test will now include up to 25 PFAS chemicals, up from the six tested in the 2013-15 study. The cooperative between the DEQ and OHA seeks to crack down on PFAS contamination that could end up in drinking water, a primary concern to both agencies.

PFAS and a family of chemicals that do not break down in the environment or in human bodies. Those chemicals are linked to cancer, reduced fertility in women and development of infants and children, among other symptoms. The chemicals have been used since the 1940s and are found in thousands of household and commercial items, such as nonstick pots and pans, waterproof clothing and firefighting foam agents.

Some plants, such as grasses, can absorb contamination when they are fertilized with PFAS contaminated material from wastewater treatment plants. This has resulted in cows producing contaminated milk in some dairy farms in the U.S. There also is evidence that when surface water is contaminated, certain PFAS compounds can accumulate in fish.

But primarily, the DEQ and OHA is concerned with contaminated sources in drinking water.

“The most likely pathway into the human body is through drinking water, and that’s why we’re doing this proactively — taking a look and see what’s in the water,” Esteve said.

A grant through the federal Environmental Protection Agency is paying for the analysis, and the DEQ’s laboratory will analyze the drinking water samples for 25 PFAS compounds, all at no cost to local cities.

While there are no enforceable regulations regarding PFAS usage, the EPA has set a chronic lifetime health advisory for drinking water of 70 parts per trillion. The OHA has developed its own health advisory levels for PFAS in drinking water that are lower, at 30 parts per trillion.

If tested, most people in the U.S. would have PFAS measured in their blood, according to the OHA. However, testing for PFAS exposure is expensive, and not likely to be covered by insurance.

Health risks from long-term exposure to PFAS chemicals can affect growth, learning and behavior of infants and children, reduce a woman’s chance of getting pregnant, interfere with the body’s hormones, increase cholesterol levels, affect the immune system and increase the risk of cancer.

The DEQ has not yet set a timetable for the completion of the testing. Results from testing can take upwards of a month between collection and a finished analysis, according to Esteve.

“This is the pilot, these first 20 we want to see how that goes,” Esteve said. “And then based on how that worked and what results we get, that will inform the time table going forward.”