Driver shortage frustrates trucking industry, agricultural producers

Published 7:00 am Thursday, February 24, 2022

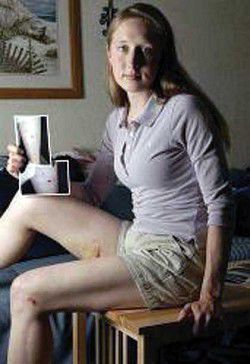

- Arsenault

PORTLAND — Jason Nord poked his head out the window of a hulking Freightliner 18-wheeler as he practiced backing the rig between rows of orange cones at the Western Pacific Truck School in Portland.

Trending

The exercise required the rookie driver to use skillful maneuvers to coax the truck and its trailer into a slot that simulated a warehouse loading dock. One by one, students took their turn behind the wheel while instructors on the ground offered guidance.

After previously working in construction, Nord, 41, said he can make more money as a trucker. He enrolled in the school to get the hands-on experience and training necessary to apply for his commercial driver’s license.

“Everybody knows we’re short truck drivers,” Nord said of the industry.

Trending

For years, the trucking industry has suffered a debilitating shortage of drivers. With the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic, that shortage has mushroomed into a crisis. The American Trucking Association estimates the driver shortage peaked this year at 81,000 — up from 51,000 pre-pandemic.

With fewer trucks on the road and port bottlenecks plaguing the supply chain, agricultural producers and exporters face spiraling transportation costs.

Sara Arsenault, director of federal policy at the California Farm Bureau, said exports that once cost $2,500 to $5,000 per container to ship overseas are now $12,000 to $30,000 per container. Increasingly, agricultural exports are being left behind as ocean carriers send empty containers back to Asia, where they are loaded with more lucrative U.S. imports.

The setbacks are vexing, Arsenault said. In one case, she said a producer was forced to make 12 trips delivering a shipment of dried fruit from the Central Valley to the Port of Oakland due to scheduling that can change suddenly and without warning.

“Our producers are certainly feeling it,” Arsenault said. “We are having huge frustrations and huge concerns.”

The truck driver shortage is a major component of the larger crisis, Arsenault said. In addition to a shortage of long-haul truckers traveling between cities, there is a shortage of local delivery drivers and even drivers who handle the chassis that shuttle containers to and from West Coast ports.

Driver shortage

Demand for drivers is so high that some companies are offering signing bonuses of up to $20,000 for experienced operators. The median pay for drivers in 2020 was $47,130, or $22.66 per hour, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

For 10 years, Jon Samson was executive director of the Agriculture and Food Transporters Conference, a unit of the American Trucking Association that focuses on critical issues affecting commodities and food.

Now vice president of conferences for the association, he said approximately 80% of all agricultural products are transported via trucks. The rest is moved primarily by rail or barge.

While the driver shortage is not new, Samson said it accelerated in the early days of the pandemic as states shut down businesses to slow COVID-19’s spread. Suddenly, long-haul truckers couldn’t even find a place to park and rest or shower as truck stops and rest areas closed.

Vaccine mandates were another source of consternation, Samson said. Though the Supreme Court ultimately blocked the Biden administration’s vaccine requirements for companies with more than 100 employees, just the threat was enough to push some truckers out of the industry or into retirement.

“We’ve been working extraordinarily hard to either bring people back, or retain the people that we currently have,” Samson said.

Drivers are also getting older. The median age of over-the-road truckers is now 46. Samson said it is imperative to recruit new blood, though federal law prohibits CDL drivers younger than 21 from participating in interstate commerce.

Instead of hiring drivers at 18, when they are fresh out of high school, Samson said they lose those first three years before they reach 21, putting the trucking industry at a competitive disadvantage compared to other trades.

“It really is crucial, and a lot of these are rural farm kids that we’re focused on bringing in as well,” he said.

Jana Jarvis, president and CEO of the Oregon Trucking Association, said one way companies are appealing to new drivers is by offering higher pay and benefits — hence the five-figure signing bonuses.

There is also much more work available locally, as e-commerce has changed how consumers shop, Jarvis said. Instead of spending weeks at a time on the road, drivers can now make local deliveries and return home to their families every night.

“The flavor of our industry has changed dramatically over the last decade,” Jarvis said.

Calling all truckers

Willy Eriksen, president of the Western Pacific Truck School, said that during any given four-week class period, recruiters from 16 trucking companies will court students during their lunch break with promises of a job once they get their CDL.

“This is the highest (demand) I’ve ever seen,” Eriksen said. “It’s always been an in-demand job, but nothing like this.”

Founded in 1977, Western Pacific Truck School is a 160-hour program that combines classroom and on-the-road training to get drivers ready for their CDL test. The school has two locations, in northeast Portland and in Centralia, Wash.

About half of all students now are sponsored by companies that pay the $6,000 tuition to get more drivers, Eriksen said.

“All of a sudden, companies are realizing there’s just nobody out there walking around with a CDL,” Eriksen said. “Companies are now scraping trying to find drivers. They’re offering big bonuses, and things I’ve never seen in the industry before.”

Alex Paliy, 23, graduated from the school in December. Three days later, he passed his CDL test and got a driving job with React Logistics, a small carrier based in Troutdale, Ore.

Paliy, whose background is in computer science and information technology, said he was attracted to trucking by the pay. He has already made two cross-country trips to Florida, hauling everything from pallets of soy protein to Duracell batteries.

There’s more to the snarled supply chain than just a driver shortage, Paliy said.

In his few months on the job, he said he has also seen understaffed distribution centers and warehouses with lines of trucks waiting hours to load and unload, indicating labor shortages in other links of the supply chain, too.

“It’s such a complicated industry with many branches of work,” Paliy said. “It’s not just drivers. You have brokers, you have dispatchers, you have warehouses, you have ports, you have cross-docks and distribution centers. All of that ties in together.”

Eriksen said the school is booked several months in advance as companies escalate their push to hire drivers.

“In four weeks, you have a career,” he said. “You could go to college for four years and not be able to make the same money you can driving a truck.”

Pilot program

In addition to higher pay, legislation included in the $1.2 trillion federal infrastructure package could pave the way for younger drivers to join the industry.

The Drive Safe Act establishes a two-step pilot apprenticeship program for drivers 18-20 years old to participate in interstate commerce. Participants must complete 400 hours of additional training, including 240 hours supervised by an experienced driver.

The program also requires trucks to be fitted with technology including active braking collision mitigation systems, forward-facing event recording cameras, speed limiters set at 65 mph or lower and automatic or automatic-manual transmissions.

“It has a significant amount of both technology requirements on the trailer itself, and a significant amount of training for the younger driver — including someone who’s also going to be sitting next to them in the cab,” said Samson, of the ATA.

He said the program will be overseen by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration, and will be running “in the near future.”

Jarvis, of the state trucking association, said she hopes Oregon carriers will consider participating to fill some of the program’s 3,000 available slots.

“It’s a heavy financial investment on the part of trucking companies to take two drivers on one delivery, but it was something our industry was very interested in supporting,” Jarvis said. “It’s an essential job.”

Not everyone is on board with the program. Opponents argue teenage drivers pose a higher risk of crashing, and the new law would do nothing to retain drivers who become burned out due to grueling schedules and long stretches of time away from home.

To recruit more drivers, the Idaho Trucking Association has a new $175,000 truck simulator that it takes to high schools around the state. The idea is to get students thinking about a career as a truck driver. The first stop was Jan. 26 at Middleton High School.

“The hands-on experience may ease some concerns and create excitement for students looking for career options,” said Allen Hodges, the association’s president and CEO. “If the driver shortage continues, this will (prevent) everyone from getting the goods they want in a timely fashion.”

Until the supply chain regains its footing, Samson, of the trucking association, said agricultural commodities risk having a shorter shelf life and higher production costs.

“It’s a complicated web, but none of it ends up being a positive for the farmer or the consumer,” he said.