Our view: The next steps for addressing nitrate problems

Published 7:00 am Thursday, September 29, 2022

The existence of nitrates in groundwater is common in many parts of the world. It’s when the concentration exceeds the level considered safe by the Environmental Protection Agency that there’s a problem.

Trending

Nitrates can occur naturally or they can come from over-applying nitrogen fertilizers, wastewater, manure and other sources of nitrogen. Crops greatly benefit from the boost nitrogen provides, but they can take up only so much. After that, the nitrogen can travel downward through the soil until reaches groundwater. There it lingers as nitrates. Nitrates found today in groundwater can be from fertilizer that was overapplied decades ago — called a “legacy pollutant.”

Too much nitrate in drinking water can lead to cancer, thyroid problems, miscarriages, respiratory infections and “blue baby syndrome,” in which a child has difficulty taking in oxygen.

Where there’s a problem, there also needs to be a game plan for solving it.

Trending

First, there needs to be monitoring to determine the scope. In many parts of the country, landowners test their well water annually to determine nitrate levels and any trends. That is a good practice for anyone with a well.

Then, reverse osmosis or ion exchange filters need to be installed as a stopgap wherever the nitrate concentration exceeds healthful levels. Water can also be distilled, a simple and low-cost method of ridding it of nitrates.

Scientists also need to pin down the sources of nitrates. Often, several sources are responsible.

Then comes the hard part. Researchers need to look for effective, affordable and doable means of reducing nitrate levels in the groundwater and preventing more nitrates from getting into it.

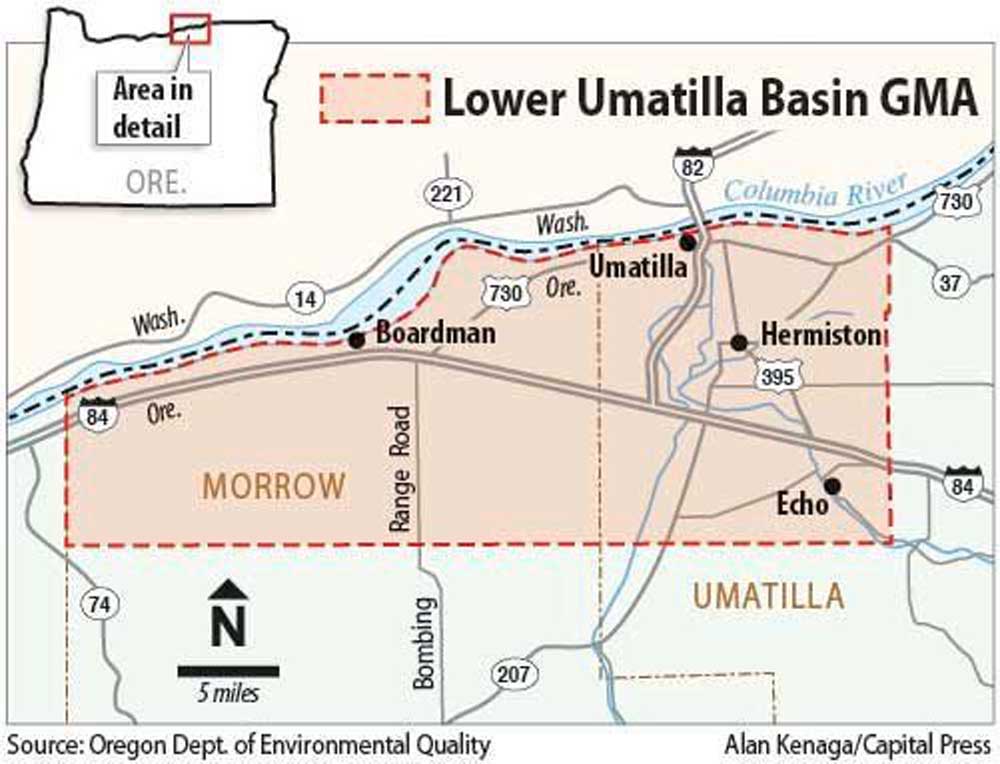

That is where the folks in the area surrounding Boardman are. They know there’s a problem in parts of the region. They know the sources of the nitrates.

And they’re more than willing to do what they can to address it, but no game plan is in place to provide farmers and food processors with best practices. They also need to determine the best and most cost-effective means of reducing nitrate levels in the groundwater.

“To date, there’s been a ton of time and resources spent pointing the finger at whose fault this is,” said J.R. Cook, founder and director of the Northeast Oregon Water Association. “We’re all at fault. Now, what’s the solution?”

It’s been 32 years since the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality designated the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area. About 44% of the test wells in the area have nitrate levels higher than the EPA limit of 10 milligrams per liter. Some are more than six times the limit.

The time has come to determine what other parts of the world have done to address nitrate problems and how successful they were. Surely, researchers have come up with a way to address this problem.

Then they need to act.