The ABCs of avalanches: Preparation, caution are the keys

Published 10:00 am Thursday, December 15, 2022

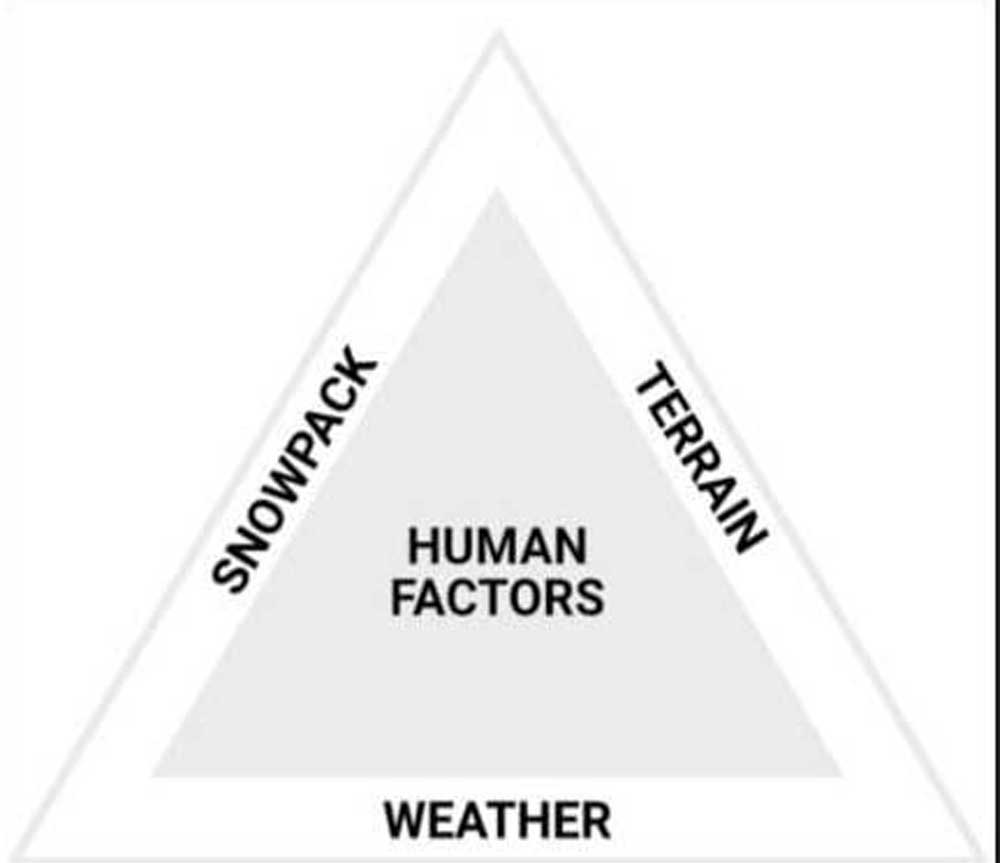

- Avalanche Triangle

JOSEPH — The snow started falling in Wallowa County in late October, with the first flakes continuing into early November.

That was good news for recreationists who count on ample amounts of snow for skiing, snowmobiling, snowshoeing and other wintertime activities.

But, warned Victor McNeil, director of the Wallowa Avalanche Center in Joseph, it’s an early-season scenario that potentially increases the risk of avalanches.

That’s part of the reason why more than 50 people recently crammed into the Winding Waters River Expeditions’ Boathouse Shop to hear McNeil offer a briefing about avalanche risks, the red flags that warn of possible slides and what to do if you get caught in one.

The briefings have become an annual tradition, but for the past couple of years, the COVID pandemic has pushed them into online settings. The recent session at the Boathouse Shop was the first in-person briefing in three years.

McNeil began spending winters in the Wallowas in 2009, and has worked as a professional ski and mountain guide for the past 12 years. He’s earned a Level 3 avalanche certification through the American Avalanche Institute. When not out backcountry skiing, he’s working on his snowmobile skills and how to develop better avalanche education for motorized backcountry users.

Attendees munched on pizza from M. Crow and sipped on beer from Terminal Gravity as they listened to McNeil describe why the region has developed what he called a “persistent avalanche problem” this season.

It starts, he said, when the area gets snow in the fall that doesn’t melt. This season, that early snowfall was followed by two weeks of a high-pressure system and cold temperatures — but no additional snow. That snow on the ground becomes weak, he said; experts call it “faceted snow” and it’s noncohesive.

Beginning in late November and continuing through December, the region has experienced consistent snowfall.

“So we now have 2 to 5 feet of snow that is more cohesive sitting on the top of the weak snow that developed during the high pressure in November,” McNeil said. “It’s like building your house on a poor foundation; it’s likely not going to hold up. We call this a persistent avalanche problem, because it doesn’t go away overnight, and can plague us for weeks or months.”

And the Northwest is due this winter for potentially more snow than usual, according to the National Weather Service in Pendleton. For the third straight winter, forecasters say, a La Niña weather pattern is in effect, likely creating cooler temperatures and increased precipitation across the region.

All the more reason, McNeil said, for recreationists to brush up on their avalanche basics — including how to watch out for red flags that signal potential danger, what to do when caught in a slide and the essential equipment that could mean the difference between life and death.

Five red flags

An avalanche is defined as a mass of snow sliding, tumbling, or flowing down an inclined surface. No one knows for sure how many avalanches occur in a given year, but they’re not infrequent.

There are different types of avalanches — and they all can be dangerous — but the type of avalanche responsible for the vast majority of deaths in North America is known as a “slab avalanche,” in which a cohesive slab of snow breaks away and begins to slide as a unit on the snow underneath. A typical slab can be the size of half a football field and ranges from 1 to 3 feet deep. Slabs can accelerate to speeds up to 80 mph within six seconds of breaking away.

So, McNeil said, recreationists need to be alert for what experts call the five red flags of avalanche danger:

• New snow: Estimates are that 90% of human-caused avalanches occur during or within 24 hours after a storm. So the first 24 hours after a storm call for additional caution.

• Signs of recent avalanches: Have there been recent avalanches in the area? Where? Resources such as the Wallowa Avalanche Center offer avalanche forecasts and collect observations from recreationists.

• Collapsing or cracking snowpack: If you feel the slope collapse under your feet or hear the unmistakable “whumpf” sound, that’s a sign of unstable layers in the snowpack.

• Rapid rise in temperature: The snowpack doesn’t have time to adjust to rapid increases in temperature. Use extra caution on the first warmer day after a storm cycle.

• Strong winds: If strong winds between 20 to 60 mph are or have recently been blowing, they can create dangerous slabs and increase the avalanche danger.

Rescue gear

Here’s a sampling of the rescue gear you should consider taking on your next excursion to the winter backcountry:

• Transceiver, shovel, probe: These items will help you survive if you get smothered. Be found and dig out. Be wary of interference, which can occur when your transceiver is too close to devices that use electricity. If you have no signal, turn other devices off so your transceiver works.

• Airbag: This will inflate and give you a better chance of getting air if encased by heavy snow.

• Satellite communication: A useful piece of equipment when in the backcountry.

• Rescue Tarp: An essential piece of gear for backcountry skiing. This multi-purpose tarp/sled can be used as an emergency shelter or bivvy sack if you need to spend the night outside, and can also be used to package an injured patient and slide them to out on the snow to medical care.

• First Aid/CPR: Knowledge of lifesaving skills are critical in the backcountry. Know how to save a life.

If you get caughtIf, despite all your preparations and precautions, you’re caught in an avalanche, here’s McNeil’s advice:

• Fight: Move to the side or try to run uphill. Swim if you get in the thick of it.

• Get off the slab: Try and get off to the side, grab something solid such as a tree or rock.

• Pull your airbag: These systems function by inflating an airbag to about 150 liters via compressed air (or gas) or an electric fan, which help the user stay on the surface of the snow in the event of a slide.

• Protect your airway: Creating an air pocket will give you space to breathe once the snow has settled. Cupping your hand over your mouth while caught in an avalanche will create an air pocket. You can also expand your chest out by filling your lungs with air which will give you more space to breathe.

• Be a Zen master: In any dire situation the first instinct often is to panic, but if you can relax in the situation and clear your head, your ability to cope will be vastly increased.

The mission of the Wallowa Avalanche Center is to keep winter backcountry travelers safe in the mountains of Northeast Oregon through education, avalanche advisories, mountain weather information and observations.

The center begins biweekly avalanche forecasts in the fall after enough snow accumulates in the mountains for on-snow travel in the backcountry and continue them until early April. It also offers a variety of classroom and field-based educational programs, including instruction specifically aimed toward youth, backcountry skiers, snowmobilers, and professionals.

The center is offering four scholarships this season for avalanche education. The deadline for applying is Thursday, Dec. 15. Go to the Wallowa Avalanche Center’s website for more details about how to apply.

Sponsors help cover the costs of avalanche forecasting for specific areas: Eagle Cap, the Wallowas, the Elkhorns and the Blues. For more information about sponsorships, contact the center at 503-329-6603 or email

info@wallowaavalanchecenter.org.

The center’s website is https://wallowaavalanchecenter.org/