Two brothers, a murder and the path to redemption: Why Jason Thomas forgave the Redmond 5

Published 5:45 am Sunday, September 17, 2023

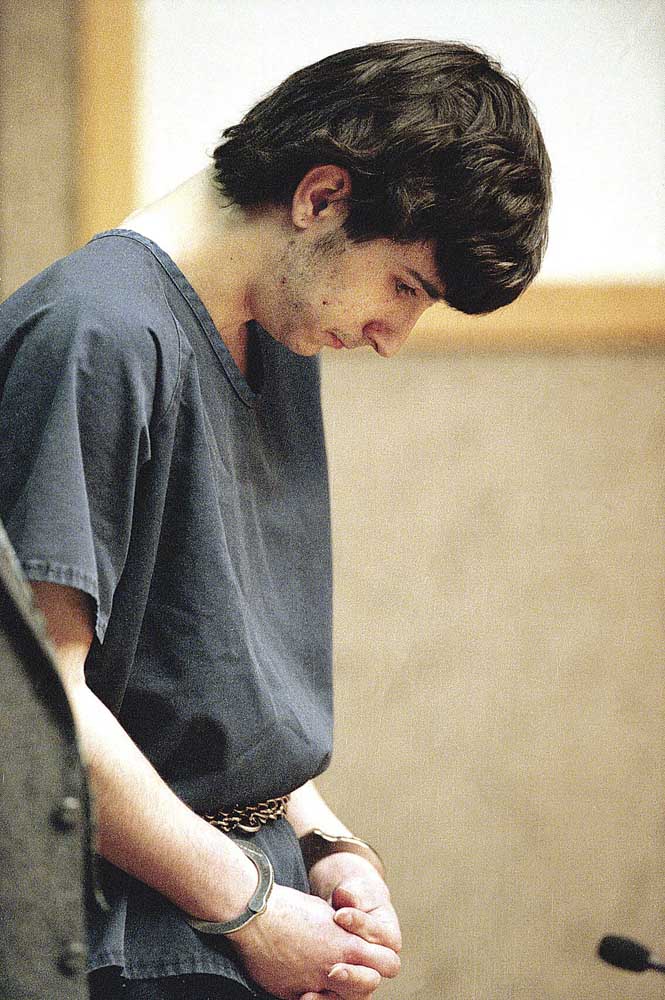

- Adam Thomas at his indictment hearing in 2001.

BEND — He had returned to the prison again and again to see his brother. Fifteen years of visits, and now the inmate who had known him since childhood was at risk of dying behind bars.

So Jason Thomas sat down at his desk and typed an email to Oregon’s governor. He described the worst day of his life: the day his younger brother, Adam Thomas, and four other teens murdered their mother at her home along the Old Bend-Redmond Highway.

Jason was tall, Catholic, conservative, an electrician in his 40s with seven kids. When the five teens were sentenced for the 2001 murder of Barbara Thomas, he firmly believed in law and order. The teens should serve every year she had left to live, he remembers thinking. Every year they stole from him.

But as he typed his letter in June 2022, then-Gov. Kate Brown was weighing clemency — postponed punishment, lesser sentences, forgiveness — for inmates statewide. And now Jason, changed by the years since the murder, wrote with the support of his family.

“We are of the opinion that all of them, who were adolescents at the time of the murder, deserve to have a chance to live the rest of their lives as free people,” he wrote.

Longtime residents still call them the Redmond 5. The two girls, Lucretia Karle, 16, and Ashley Summers, 15, were sentenced to 25 years in prison. The three boys, Justin Link, 17, Seth Koch, 15, and Adam, 18, got life without parole.

It remains one of the region’s most notorious crimes, ending with the death of a caring, well-loved widow who worked at a local outlet mall, who loved fishing and mountains and her children, who instilled in her boys a love of books. Barbara Thomas was 52.

What Jason endured in the weeks after her murder would never leave him.

He had walked into his mother’s home about a week after the murder to a nightmare. He spread sheets over the blood in the living room to hide it from his family.

His father had died of cancer four years earlier, so the job of what to do with the remnants of his mother’s life — her clothes, her makeup, her crafts and stamps, her bills and money, her funeral plans and burial — fell largely to Jason.

But now, Jason, who still referred to his mother’s killers as “the kids,” wanted Brown to grant clemency to each of them. To the man who first proposed the murder. To the man who pulled the trigger. And to his brother, who stood by and did nothing to stop the violence.

He ended his email describing a life that few could understand.

“As a family member of both the murderer and the murdered, not only do I mourn my mother’s loss, but am saddened that there are many men and women in prison serving long sentences as the result of immature decisions made as children,” he wrote.

Then he sent it.

By June 2023, four of the Redmond 5, having demonstrated they had changed, were free. Only his brother remained in prison.

The murder of Barbara Thomas

The details of the crime are well-known.

During a spring break filled with drinking and smoking, the teens had decided to drive to Canada and get into the marijuana business. Their plan quickly unraveled when they lost the car keys at Barbara’s house on March 26, 2001. After trashing the house in a frantic search, Link proposed they kill Barbara so they could steal her car, prosecutors say. Each began to make plans.

When Barbara came home, Koch and Adam hit her more than a dozen times with empty wine bottles. Koch handed a rifle to Adam, who refused to shoot his mother. Instead, Koch shot her once. Adam cried and nearly collapsed.

“I never foresaw myself being capable of murder,” Adam, who had no prior criminal record, later wrote. “But I am fully responsible for my actions that day.”

From the archives: The story behind the ‘Redmond 5’ murder of Barbara Thomas

They fled to Canada in Barbara’s Honda but never made it past the border. A Canadian customs inspector learned they were suspects in a homicide. They were taken to the Whatcom County Sheriff’s Office in Bellingham, Washington, where they confessed.

Sentenced as juveniles, four are released

When the Redmond 5 were sentenced, Oregon automatically tried youths accused of serious crimes as adults. Over the years, the state reported “the second highest rate of youth transfers to adult court in the nation,” according to a study by the Oregon Council on Civil Rights published in 2018, a year before this law changed.

Such practices have long ignited heated debate in Oregon. Juvenile justice reformers called the state’s penalties for youths especially harsh and costly, punishing people for crimes committed at a time when their brains had not fully developed. Law-and-order advocates demanded that the state preserve justice for crime victims by keeping youth offenders in prison.

According to the National Institute of Mental Health, adolescent brains are not fully developed until their mid-to-late 20s. A growing body of research indicates youths are likely to lack impulse control and struggle to fully grasp the consequences of their actions.

Primed by this research, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles violated the Eighth Amendment, which forbids cruel and unusual punishment.

Then, at the end of her term, Brown took actions of her own, exercising a broad use of her clemency powers with a publicly stated goal: mercy.

Parole board grants release to four Redmond 5 killers. Will society accept them?

She pardoned thousands of people convicted of possessing small amounts of drugs. She commuted sentences for about 40 people who fought the record-breaking 2020 wildfires. She made more than 70 juvenile offenders convicted in adult court eligible for parole after serving 15 years.

Her move was unprecedented and quickly sparked political backlash, often from those who argued she was disregarding crime victims and deepening their trauma.

But some attorneys argued the commutations provided second chances for people who have made progress in prison and are ready to serve their communities.

“By saying that we’re going to sentence these people to life without parole, we’re saying they have no hope,” said Jody Davis, an attorney who represented one of the Redmond 5, Justin Link, during his parole process.

The Redmond 5 benefited quickly. Brown ordered Karle’s release first, in September 2021. This year, the Oregon Board of Parole granted release to three more following lengthy hearings where they spoke about their progress and rehabilitation.

‘There’s no excuse for what I did’; Redmond 5 murderer seeks release from prison

But the governor’s clemency order for juvenile offenders didn’t apply to Adam. He was 18 at the time of the murder.

Adam Thomas: The angry son

Adam, now 40, has never spoken publicly about what happened that night in 2001. He declined to be interviewed for this story. But he wrote about his life and the crime in June 2021, when he applied to have his sentence reduced.

“To this day, the nightmare of the murder has not left me and I am emotionally affected by the memory of what I participated in,” he wrote.

As a youth, Adam was tall, skinny and awkward. Sometimes he would sit out of gym class because he had asthma. He had a “quite meager” group of friends and joined clubs for drama and the school newspaper. His dad was his best friend, so when he saw him in the hospital, dying of cancer, “my emotional wall crumbled,” he wrote.

Adam struggled to cope with his father’s loss. Raised Catholic, he stopped attending church. He listened to heavy metal music and wrote disturbing song lyrics. He stole his mother’s credit card, lashed out when she asked him to do chores and would take her car for a drive around town when she slept.

When his mother started seeing someone, Adam grew angry. “It was quite selfish and thickheaded of me to expect her to remain single for the rest of her life,” he acknowledged later.

As a high school senior, Adam spent much of his time at home, in his room, on the computer. Around this time, he met the four teens with whom he’d commit the murder.

“I was having fun getting high, driving around all over the place, staying out all night, and feeling like I was one of the cool kids,” he wrote. “I wanted to be accepted by them and I believed at that time that I was.”

Adam loved his mother, but in describing the murder, he said “one of the reasons I did not try to stop it from happening was because I had detached myself emotionally from my mom.”

He acknowledged planning the murder with the others, but wrote that he was not convinced it would happen.

“The idea seemed ludicrous, something that was merely a part of our ugly imaginations,” he wrote. “We were stupid kids attempting to ‘one up’ each other with our own murder plots.”

He added: “I found myself caught up in a pack mentality at its worst.”

Jason was in the U.S. Army, stationed at Fort Richardson in Alaska with his first child on the way, at the time of the murder. When he finally returned to Central Oregon, he sat across from Adam in the Deschutes County jail. Jason was unable to speak. He cried into the jail phone while Adam stared back from the other side of a sheet of the glass, expressionless.

Brothers rebuild relationship

Four years passed before Jason could bear seeing his brother again.

“Because he stood by and let my mother be murdered,” he recalled in September. “It took me a while to get over that.”

But one day, he drove an hour from his home in Vancouver, Washington, to the Oregon State Penitentiary in Salem to visit him in prison for the first time.

Jason was nervous when he walked up to the prison, passing the towers, the guards, the gates and the metal detector. He stepped into a big, long visiting room with knee-high tables bordered by gray chairs for inmates and red chairs for visitors. An inmate leaned over and told him he was in the wrong chair, but he was afraid to move around and draw too much attention to himself.

Then Adam arrived.

He wore denim pants and a blue shirt. He was bigger than the last time they saw each other. His hair seemed different. Jason could tell his brother was nervous, too. They hugged. Jason could feel his brother shaking.

Over the years, Jason had received letters from Adam, but they felt insincere and hollow. Now, the brothers made small talk through awkward moments. Work. Kids. Current events.

When Jason went back to his home in Vancouver, he realized that visiting with his brother wasn’t so bad.

He could go back again.

And he did, visiting his brother about twice a year on Saturdays. Slowly, he grew more comfortable. The brothers joked around and challenged each other to remember old addresses from childhood. They took photos together. They never spoke in-depth about the murder.

In time, Jason began to see changes in his brother, in their face-to-face conversations and the letters they exchanged. Adam wasn’t the inmate struggling to mature that Jason had first encountered. He sounded smarter, more sincere, like he was accepting what he had done.

Finding purpose

In prison, Adam devoted his time to reading books: self-help, mortality and ethics, philosophy, history, science and religion. He earned his GED. He tutored other inmates in writing and had his own classroom.

He joined a special interest group for the prison’s LGBTQ community. He took a class on listening and a course on love and resilience. He attended mental health therapy. He completed hospice training and sat beside dying inmates.

“It brought me face to face with how vulnerable and precious our lives are and how we all need to better understand how to care for people,” he wrote in his clemency application.

Aside from one “major” altercation at Coffee Creek Correctional Institute in 2003, he had minor disciplinary reports for possessing a radio, a rain jacket and sandpaper. For more than six years, he worked in a prison furniture factory, sometimes building special projects for the government, even an adjustable podium for the governor.

The work gave him a sense of purpose. Jason’s visits meant something more.

“Because the victim in my case was our mom, I would not have been surprised if my brother had cut off all contact with me,” Adam wrote. “His constant presence and continued love for me has been a remarkable gift these last twenty years.”

The path to forgiveness

It was more than a decade after the murder when Jason’s kids began asking questions. What happened to their grandmother? Why was their uncle in prison? His kids were asking other kids, and their parents approached Jason. He knew they needed an explanation.

When he shared what had happened, they weren’t judgmental. Only curious. They asked Jason if they could meet their uncle. Adam obliged.

So they started joining their father on his visits. Now there was another round of nervous entries to the prison, questions and small talk with Adam. School. Video games. Adam’s life in prison.

Lana Thomas, Jason’s 17-year-old daughter, felt awkward at first, making one-on-one conversation with her uncle in prison. But she never felt scared. She didn’t ask about the crime. Instead, they talked about baking and carpentry. To her, Adam was friendly, outgoing, funny.

“This is one of the only people related to my dad,” she said. “I wanted to get to know him.”

Meanwhile, Adam sent Jason’s kids handwritten letters on their birthdays, presents at Christmas, every year without fail.

“Remember not too grow up too quickly, but find satisfaction every step of the way,” he wrote to Lana on one birthday.

“Things are as fine as can be expected here … I would love to work in a bakery if I ever got out,” he wrote on another birthday.

“Never stop finding the beauty of life and the world around you,” he wrote on another birthday.

The family posted these letters on a wall beside the front door, near a framed childhood portrait of Jason’s family that hung in the hallway.

Meanwhile, Jason and his wife, Melissa, who worked in the cafeteria at a local school, began talking about the Redmond 5 on their walks. The family began praying over them together in the living room before bed. Jason imagined his brother, trapped in the depressing monotony of daily prison life: cell, work, food, bed.

“This was a crime by children, a crime of children, childish thinking and childish reasoning.”

— Jason Thomas

As his kids grew older, Jason began to see the Redmond 5 not as monsters, but as kids, much like his own. Kids who had made a terrible mistake.

“This was a crime by children, a crime of children, childish thinking and childish reasoning,” he said.

Jason remained certain of his views around law and order. However, it wasn’t so simple anymore. When Adam talked about the shame and how he blamed himself, Jason told him that he’d moved on.

“You’re the only one who’s still back in 2001 in that house,” he recalls telling Adam. “You’re still there. You’ve gotta let it go.”

Jason didn’t want to live his life harboring anger and resentment. He wanted Adam to be part of his family. He and Melissa thought about their Catholic faith and one of its central tenets: forgiveness.

“If I don’t forgive, then I’m keeping all that condemnation on myself,” Melissa said. “We have to forgive. And it feels good.”

By embracing forgiveness, Jason realized that he wanted each of the Redmond 5 to live their lives as free people. He didn’t condone their actions but felt justice had been served. Enough was enough.

“Over time, all of us have forgiven the kids for what they did, and we really wish them the best,” he wrote in his email to Brown.

Jason is not Barbara’s only family member who feels this way. Though they declined to be interviewed for this story, Barbara’s brother, Rod Jones, and his family also wrote to Brown’s office, supporting clemency for the Redmond 5.

“It is the only way this nightmare will ever come to an end,” they wrote in one email.

In another letter, they said of Adam: “It is our wish, that he be allowed to request parole after serving 25 years … Barbara Thomas was Rod’s sister, and we believe this is what she would have wanted.”

‘Redmond 5’ murderer Justin Link will be released from prison in April

When Link was up for parole, Jason called his lawyer and told her that he was praying for him. Link worked with Adam in the prison. After the state granted Link release on March 7, Jason told Adam to relay a message to Link: Go on. Do good. Don’t screw it up.

The state has since released four of the Redmond 5: Karle on Sept. 30, 2021; Link on April 28, 2023; Koch on June 16, 2023; and Summers on June 30, 2023.

“Are they all going to get out and be great people? I don’t know. But they’ll have a chance now.”

— Jason Thomas

“Are they all going to get out and be great people? I don’t know,” Jason said. “But they’ll have a chance now.”

Renewed hope for freedom

When Adam first arrived at the prison in 2003, he thought he would die there “and nothing I did would ever change that.”

What was the point of living?

Now, with the laws having changed, he had “a renewed hope for my potential release,” he wrote in his application for clemency.

“I will spend the rest of my life reflecting on and trying to make up for what I did on March 26, 2001,” he wrote. “Will I spend the rest of that life behind these walls? I do not have the power to answer that question.”

So the question went to those who do.

Responding to Adam’s application for a reduced sentence, the Deschutes County District Attorney’s Office said in a letter to Brown that Adam “deserves credit for developing and maturing while in custody.” But prosecutors requested Brown keep his sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole. In their opinion letter to the governor, prosecutors also acknowledged they would be comfortable with a review of Adam’s sentence after 30 years, per Oregon’s current laws.

But Brown granted Adam’s request, making him eligible to apply for parole in 2026.

In the twilight of her term, Brown wrote a clemency letter describing the cases of dozens of inmates seeking release. She said Adam had “demonstrated excellent progress and extraordinary evidence of rehabilitation.” She said she considered input from the victims — Barbara’s family — in her decision.

Ultimately, she wrote that keeping Adam in prison without the opportunity to apply for release on parole “does not serve the best interests of the State of Oregon.”

The Oregon Board of Parole could still say no.

In prison, Adam’s been saving up money so that he can support himself should he be released. If that day comes, Jason told his brother that he can live with him and his family until he’s ready to live on his own. Adam told his brother he would want to live in Coos Bay, on the Oregon coast, the town where they lived before the murder.

Why?

“Because that is where he was happiest in his childhood,” Jason said.