Pendleton man coping with Alzheimer’s disease considers end of life options

Published 5:00 am Friday, April 19, 2024

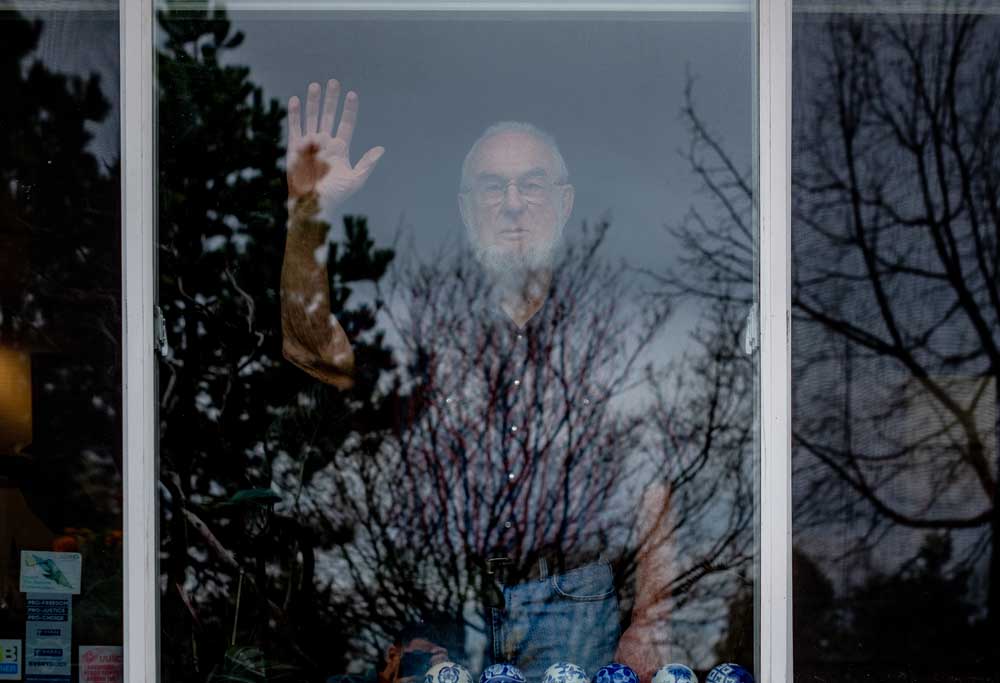

- Andrew Clark looks out the window at the front yard of his home in Pendleton on March 22, 2024.

Andrew and Barbara Clark are grappling with what it means to grow old as a couple while facing the added burden of Andrew’s Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

Trending

Andrew, 83, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment in 2019. His impairment has since been confirmed to be caused by Alzheimer’s through testing conducted by Oregon Health and Science University. Andrew is in the early course of the disease, which affects the brain gradually and impacts memory, thinking and behavior. With time, it can also impair swallowing and breathing.

Barbara, 83, and Andrew, who have been married for nearly 55 years, face the challenge of his mind declining, despite his body staying healthy. He has enrolled in four clinical trials through OHSU with the hope of contributing to research that eventually helps others in similar situations. And through it all, Barbara has become his primary caregiver, despite her own ongoing health problems.

Burden and beauty in caregiving

The Clarks live in the Pendleton home they have owned for years. It’s not the farm house they moved into in 1973 when they arrived with their eldest child after living for years in rural Tanzania, but it is close to McKay Creek National Wildlife Refuge and has plenty of trees and plants to offer its own sort of privacy. The pot of African violets sitting on the kitchen counter near the south-facing window is thriving, as is the large maple tree in the backyard.

Their walls are covered with framed photos of their family — mostly their grandchildren — and reminders of the years they lived in Africa, such as the map of the Serengeti and a quilt of the continent made for Andrew by a friend.

Every month, Barbara takes part in a virtual support group for caregivers of people with dementia. Advocating for caregivers like herself has become an integral piece of her experience with her husband’s disease.

Six stress reduction tips for caregivers during National Stress Awareness Month

Stress doesn’t just affect your mood — it can have long-term health impacts as well if you don’t take steps to manage it constructively.

For individuals who face the stressful task of caring for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia-related illness, the Alzheimer’s Foundation of America is offering six stress reduction tips for caregivers as part of April’s National Stress Awareness Month.

Family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s and related dementias are at greater risk for anxiety, depression and poorer quality of life than caregivers of people with other conditions and provide care for a longer duration of time, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

AFA offers these six stress reduction tips for family caregivers:

• Be adaptable and positive. Your attitude influences stress levels for both you and the person you’re caring for. If you can “go with the flow,” and avoid fighting the current, that will help you both stay relaxed—conversely, becoming aggravated or agitated will increase the chances that your person will as well. Focus on how to adjust to the situation in a constructive way.

• Deal with what you can control. Some things are totally out of your control. What is in your power to control is how you respond and react to these outside factors. Concentrating on finding solutions can help make the problem itself a little less stressful.

• Set realistic goals and go slow. Everything cannot be resolved at once, nor does it need to be. Don’t hold yourself to unrealistic expectations. Prioritize, set practical goals, do your best to achieve them, and take things one day at a time.

• Mind your health. Inadequate rest, poor diet, and lack of exercise can all exacerbate stress (and cause other health problems as well). As best you can, make it a priority to get sleep, eat right, drink plenty of water and find ways to be active. You cannot provide quality care to a loved one if you don’t take care of yourself.

• Clear and refresh your mind. Exercise, yoga, meditating, listening to music or even taking a few deep breaths can all help relax the mind and reduce stress.

• Share your feelings. Disconnecting from your support structure and staying bottled-up increases stress. Whether it’s with a loved one, trusted friend or a professional, don’t be reluctant to talk about your stress, because that can actually help relieve it.

AFA’s Helpline, staffed entirely by licensed social workers who are specifically trained in dementia care, can provide additional information and support for families. The helpline is available seven days a week by phone (866-232-8484), text message (646-586-5283) and web chat (www.alzfdn.org).

“I think a key is: look for the things at any given time that you both have enjoyed together and do those things,” she said. “I see changes from his doing everything himself in the past to being willing to say, ‘I need help with this.’ In his case, so far as I see his transition (and) the direction he’s going in, right now, we’re in a phase where he’s a happier person and we share more humor than we’ve shared in a long time.”

Barbara has taken four virtual dementia caregiver courses from Rod Harwood, the older adult behavioral health coordinator in Northeastern Oregon for Greater Oregon Behavioral Health, Inc., who also runs her monthly support group, since 2020. Harwood’s classes helped Barbara learn techniques to support Andrew as well as offered emotional support by connecting her to people facing similar challenges.

“What we learned today is we both have dementia,” she said during a conversation on March 15. “The way he put it is, (Andrew) has it on the inside, I have it on the outside.”

Harwood said caregivers of people with dementia have higher rates of suicide compared to those who care for people who don’t have dementia. His work as a dementia educator and consultant is just one aspect of his role with GOBHI, which is part of a broader, statewide initiative to support older adults.

“During this journey with their loved one, their own health is being compromised,” he said. “They don’t have the time to even look after their own needs.”

Because of the challenges that come in every aspect of life — emotionally, physically and logistically, to name a few — Harwood runs support groups and caregiver training courses throughout his assigned region, and he helped start monthly group meetings in Baker City and John Day.

The support groups and education is “so vital for them to survive,” Harwood said.

“My hope is eventually not only having the education and support groups for these folks, but I would love to see, in Pendleton and in my other communities, respite care sites where they could bring their loved one, whether it’s one day a week or a few hours on one day or several days a week, where they can have them there while they go and take care of themselves,” he said.

The only respite care site in Eastern Oregon, to Harwood’s knowledge, is in Hood River. He hopes these will open elsewhere because they offer a chance for caregivers to take care of themselves without trying to also take care of their loved ones. The sites offer caregivers physical and mental support.

Barbara, as Andrew’s primary caregiver, is handling some — or even many — of the tasks that used to be her husband’s responsibility while also helping him manage his condition. She said she’s taken Harwood’s class four times because each time is different and all are useful.

“Every time I’ve taken the class, I realize we’re now at a little different stage, and I’m hearing things that I didn’t pick up before,” she said.

“The caregivers are in very, very difficult circumstances,” Andrew added. “Here in Pendleton, we are so fortunate that Rod (Harwood) is here to do things like this.”

In the most recent iteration of Harwood’s course, one of the major takeaways Barbara had was that taking care of herself is part of taking care of her husband, a notion Andrew wholeheartedly supports.

“We know these two women, our friends, who have just had an awful time,” he said of their friends, who had been caregivers of loved ones for a long while. “And so I distinctly do not want Barbara to have to go through that. That’s a goal.”

He wrote out four aims he has for aging with Alzheimer’s: be as happy as he can, be open about his experiences, avoid depression and anxiety as much as he can, and — maybe most important to him — be as easy to be cared for as possible.

But people with a cognitive terminal disease, like Alzheimer’s, are not eligible for some of the same choices as people with physically terminal diseases, such as cancer.

A pathway to dignity for Alzheimer’s patients?

Oregon enacted the Death with Dignity Act in October 1997. It “allows terminally ill individuals to end their lives through the voluntary self-administration of lethal medications, expressly prescribed by a physician for that purpose,” according to the Oregon Health Authority website.

In 2023, 560 people received prescriptions for lethal doses of medications under the act, though they no longer need to be Oregon residents. As of late January 2024, OHA received reports of 367 people in Oregon who died from such prescriptions in 2023 — an increase from 304 in 2022 (30 of the 367 had received the drugs in previous years). Most of these patients had cancer and were older than 65.

Death with Dignity requires the patient to be a terminally ill adult, be expected to die within six months and be “capable of making and communicating health care decisions.”

It’s that last part that puts a snag in Andrew’s plans to make his disease progression as easy as possible for Barbara.

Alzheimer’s can lead to behavioral or mood changes in people as the disease progresses. When they become disoriented or confused, especially, they can become angry or aggressive — even violent — in situations they otherwise would be fine with.

Andrew is early in the course of his disease and it has not had much of an impact on his behavior, decision-making capacity or mood. But it is something he and Barbara are worried about. Because Alzheimer’s affects people’s ability to think and make choices, he will not be eligible for death with dignity by the time he’s within six months of dying.

He could, in theory, go into a care facility when he’s no longer himself. But he’s opposed to that option.

“It’s a waste of money because this is an absolutely fatal disease, no questions asked,” he said. “So, why should we spend thousands and thousands of dollars keeping a brainless carcass alive?”

He wants Barbara to be able to use their savings for the things that make her happy, not on keeping his body alive.

The couple said they know people in similar situations who have, rather than wait for their decision-making capacity to diminish completely, chosen to pursue what they called “death by self-starvation,” also known as Voluntary Stopping of Eating and Drinking.

The process takes a few weeks, and the person choosing to do it decides not to eat anything, instead sticking with water or ice to keep them reasonably comfortable. Andrew said he’d much rather have a legal avenue — like the Death with Dignity Act — to pursue a calm death while avoiding expensive facilities, just like any other terminally ill person.

Andrew and Barbara’s daughter, Mary, who lives in New York City, did some research on death with dignity for her dad, as he’d prefer not to follow the starvation path.

Mary found that not everywhere has the same standards for death with dignity. She read “In Bloom: A Memoir of Love and Loss” by Amy Bloom, which follows one couple’s story of finding death with dignity in Switzerland for Bloom’s husband, who had Alzheimer’s.

In Switzerland, assisted suicide is legal as long as it’s not for selfish reasons, regardless of the person’s condition.

Who to call?

• Call 988: Dialing this new three-digit number will connect you with a counselor 24 hours a day, seven days a week, any day of the year. If you’re in crisis, don’t hesitate to call.

• Call 911: In an emergency, the local dispatch center can help you get the help you need.

• Call 800-698-2392: The David Romprey Warmline, operated by Community Counseling Solutions, is not a crisis intervention service. Rather, it is a peer support program that connects callers with trained peer counselors who have lived experience in dealing with suicidal feelings, mental health issues, addiction and other life challenges. The toll-free number is staffed from 8 a.m. to midnight every day.

• Call 541-962-8800: This is the number for the Center for Human Development crisis intervention line. Crisis intervention is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, by calling the number and pushing option 6. CHD is a private, not-for-profit health organization located in La Grande that provides alcohol and drug, environmental health, mental health, public health, developmental disabilities, prevention and veterans services to the residents of Union County in Eastern Oregon.

There, Andrew could maybe have the death he hopes for, just not in the context and location of where he wants it, which is at home where it would be easier to handle for Barbara and their family. Furthermore, it could take years to go through the death with dignity process abroad, Mary said, and his staunch opinion now could possibly change as his mind does.

“I think what makes this so hard is that where my dad is now could be very different from where he’s at, say, three years from now,” she said, “and where he’s very unequivocal now about the death with dignity and all of that, is he really going to feel that way three years from now? It’s just really hard to know.”

For now, then, Andrew hopes to convince those in charge of Oregon’s rules to adjust them to include the possibility of death with dignity for people like him, who don’t want a “healthy body that becomes mindless and keeps on living.”

Getting ready to die

Thinking about the negative sides of his disease can be challenging for Andrew. By nature and choice, he tries to see the best in situations. His list of how he wants to handle his disease is straightforward and honest, and it centers on living as happily as he can for the time he has left.

But even when he doesn’t acknowledge it, the reality is that his brain is dying before his body is ready to go.

“There’s irritation that you can’t think of a name or where you put something,” he said, “and there’s disappointment about inability to do something, and looking down the road to getting worse and worse and worse is unpleasant.”

He’s still learning, though — learning to ask for help from his friends and family, learning to find joy in the activities he can still do, learning to grapple with the emotions he’s experiencing.

“It’s kind of a foundational issue because, you know, I’ve had a good life,” he said. “I’ve had productive jobs, I’ve been very happy with our marriage and our kids and everything else, and letting all that go before my body dies is, yeah, there’s an element of grief in that.”

But for Andrew, the sadness is handily outweighed by the happiness woven throughout his days. He often makes self-deprecating jokes or witty remarks. He logs into his virtual consulting meetings in the middle of the night, since it’s the middle of the day in Africa. He teases his wife and children. He gardens and goes bird-watching. He falls asleep next to the love of his life.

As Andrew considers what his final years will consist of, fear of death isn’t even a factor.

When he was a young man, he was driving with his family in Kenya after being stung many times by bees and having an intense allergic reaction. Andrew recalls his vision darkening — describing it as “this perfect, beautiful, dense blackness” that closed in slowly, gently, peacefully.

It’s based on this experience that Andrew does not worry about what it’s like to die.

“I’m not afraid of dying at all. I have a disease that’s invariably fatal,” he said matter-of-factly, shrugging. “How can I live out whatever is left, which is limited? How do we handle that? So this is what I would share with someone else who is at this stage of Alzheimer’s disease.”

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a two-part series on living with Alzheimer’s. The stories explore the experience of aging with the added burden of dementia for the person with the disease as well as their loved ones.

Interested in OHSU’s clinical trials?

For a full list of clinical trials, go to bit.ly/ohsutrials.

For the trials focused on aging and Alzheimer’s, go to bit.ly/ohsuaging.