‘New Idaho’ still improbable but would sway U.S. politics

Published 2:24 pm Tuesday, October 11, 2016

- ‘New Idaho’ still improbable but would sway U.S. politics

A year after La Grande farmer Ken Parsons proposed Oregon and Washington’s eastern counties join Idaho, the idea is no closer to reality.

“I haven’t heard a peep from anybody in probably six months,” he said Monday.

Parsons hopes the idea might gain new legs after Election Day, however. The concept captured the region’s imagination last year, spawning news articles and discussions of “what if” around the Pacific Northwest, because rural conservatives felt Boise might be more receptive to their ideas than Salem or Olympia. That feeling tends to be exacerbated by watching election results roll in.

Even if the idea remains nothing more than a hypothetical, those “what if” conversations offer an interesting political science exercise when looked at through the lens of the upcoming election.

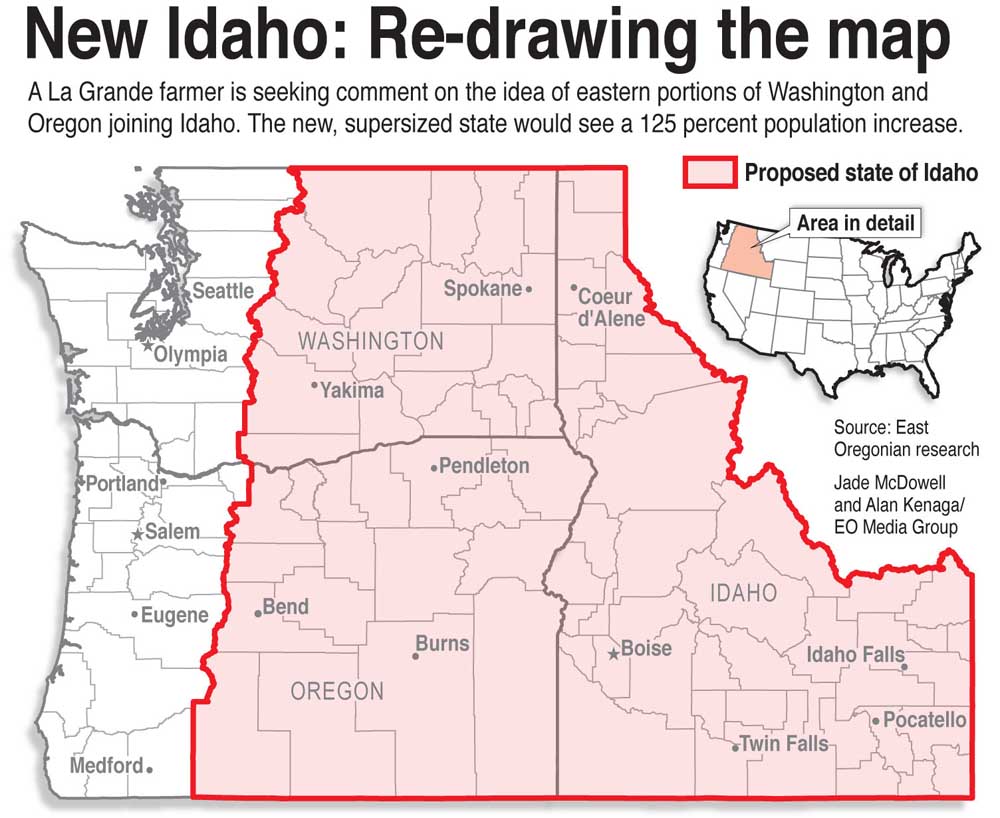

One hypothetical model would see the 17 Oregon counties east of Hood River County and the 20 Washington Counties east of King County join Idaho. That scenario would see Oregon’s population drop by about 13 percent and Washington’s population by 22 percent, while Idaho’s population would rise by 125 percent to 3.68 million.

Since the 435 seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned every 10 years based on the states’ population count in latest census, Washington would likely lose two of its 10 representatives to Idaho, and Oregon could possibly lose one of its five representatives to another state.

Electoral College votes, meanwhile, are based on the number of senators and representatives a state has serving in Washington, D.C. If reliably blue state Washington lost two representatives and reliably red state Idaho gained two, future Republican presidents could count on another two “safe” Electoral College votes in the foreseeable future — possibly three, depending on whether Oregon grew enough to hang on to all of its representatives. In a tight race like 2016, it could make a difference.

The odds to all of that happening are slim to none, however. And Parsons understands that he’s fighting an uphill battle. But he did say he was encouraged by what seemed like genuine interest from a variety of Malheur County food producers who told the media last fall that they would join Idaho in a heartbeat if offered the chance.

“Everything about Malheur County is more identified with Idaho,” Owyhee Produce general manager Shay Myers told the Capital Press at the time. “I wish I knew how to actually make this happen.”

If Malheur County led the way, Parsons said, it was possible a handful of other counties would be on board with supporting an effort to redraw state lines.

“It all comes back, to me, to Malheur County,” he said. “If they don’t want to move into Idaho I don’t see any other counties having the economic and political incentive.”

Parsons said he is looking to be more of a “facilitator” than a leader on any movement toward secession, which is why he made a Yahoo group on the issue, which later spurred a Facebook group called “E. Washington/E. Oregon join Idaho.”

That group drew 240 members, who have discussed topics such as messaging (they prefer talk of “shifting boundaries” to “seceding”) and the differences in responses by Idaho, Oregon and Washington on political questions such as allowing Syrian refugees into their state.

“One of the nice things about having Eastern Washington and Oregon be a part of Idaho, is that (maybe) people on the east side would stop viewing Democrats as awful Seattle and Portland liberals, but as Spokane or Boise moderates who want to reach a reasonable compromise,” page administrator Dan Wallace wrote.

Parsons said even if the boundaries between the states never do change, generating public discussions around the issue sends a message to Democrats in Salem and Olympia that they shouldn’t just run over the concerns of Republicans representing the eastern counties on topics such as minimum wage.

“It’s saying, ‘Listen, the people in eastern Oregon and eastern Washington are upset. They don’t like what you’re passing,’” he said.