Camp Logan established to protect settlers

Published 4:00 pm Sunday, January 26, 2003

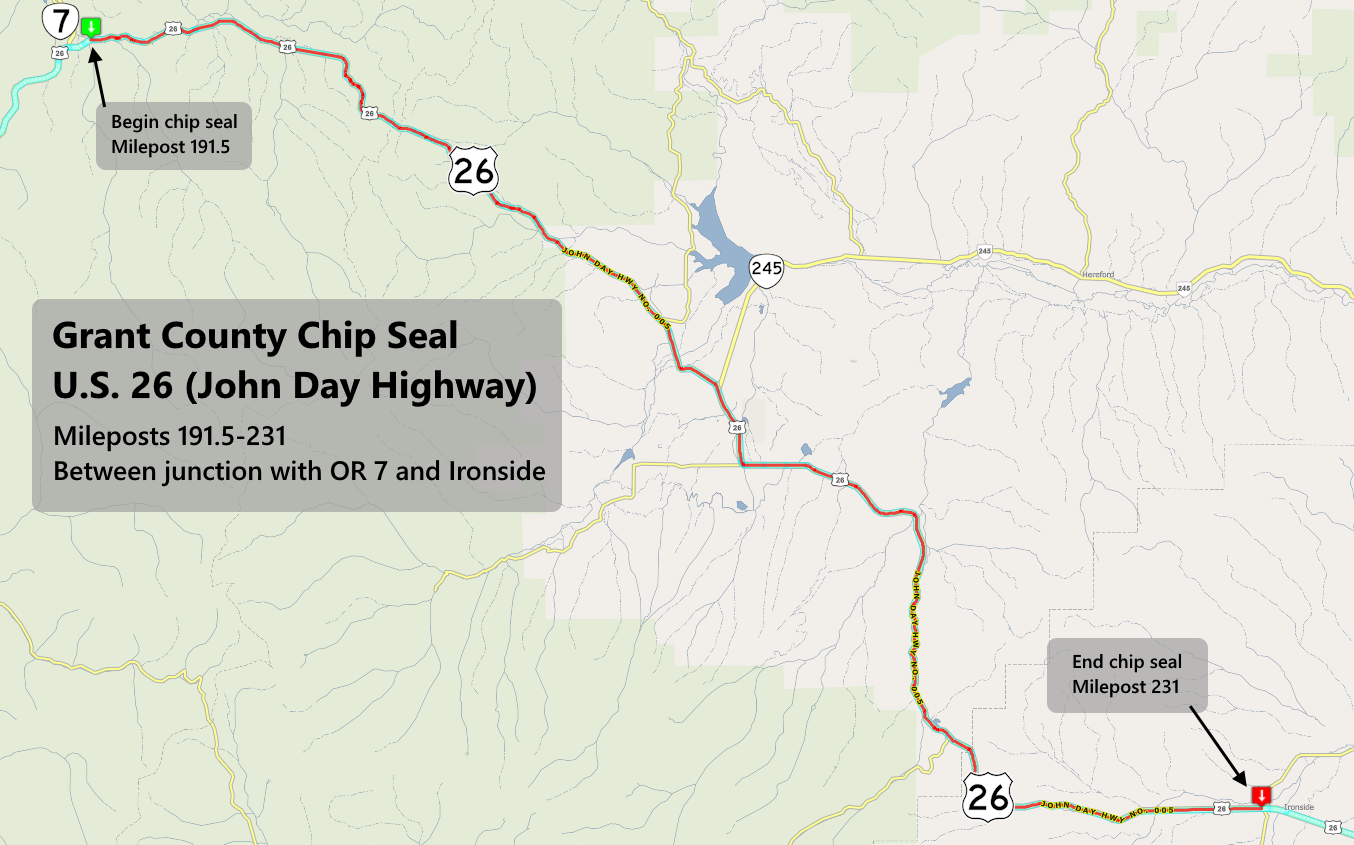

- The present-day Prairie City History Club (shown above) is planning a re-enactment during the first Camp Logan Day planned for Saturday, May 17, with activities such as haywagon ride, troop inspection, drill and artillery demonstration, tour of the camp, early-day skills demonstrations (blacksmithing, candlemaking, dollmaking, campfire cooking and more), barbecue, and old-time fiddlers music and dancing. Camp Logan is located approximately three miles south of Prairie City on the county road to Strawberry Lake. Members pictured include: (front row, from left) Chancey Groves, Tim Dahlen, Daniel Soupir, Christina Butler, Daniel Rodgers and Jamison Soupir. Back row, from left: Larry Whitley, Michael Thompson, David Ribero, Meaghan Keffer, Tylor Zemmer, Sarah DeRosier, Andrew Demko, Dianne Lesniak and Donald Teel. Contributed photo

Tucked away in Grant County history is a chapter seldom mentioned in any books. However, without this place and the men who served there, the mining, ranching and settlement of the John Day Valley would not have developed at such a rapid pace.

According to maps of the early 1860s, Eastern Oregon was labeled an unexplored territory better left to the population of Indians. It was recommended that white settlers not stay, but pass through to the Willamette Valley. Needless to say, the discovery of gold in the 1860s caused an explosion of immigrants to this unsettled area. Towns sprang up immediately throughout Eastern Oregon. With pressure from the onslaught of white civilization, bands of native tribes preyed on small groups of travelers and stole wandering livestock. Although they never attacked reasonably fortified ranches or settlements the so called “depredations” of a few Indian bands aroused enough fear in the growing white population that the settlers demanded some form of protection.

The Department of Columbia had been established by the military in 1965 and consisted of what is today Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and later, Alaska. Department headquarters was at Fort Vancouver. In response to the outcry for better and safer travel, the Oregon Military District under Captain S. Harney, established many linking forts and “camps,” between The Dalles and Boise. The camps were to be limited in size and would provide a temporary presence that would aid and escort wagon trains of immigrants and goods moving through Indian country. Protective forces were stationed at Camp Watson near Antone, which was established to protect the The Dalles to Canyon City Road. Camp Logan, which was to be a sub-post of Camp Watson, was to protect those traveling on to Boise. Camp Logan may have been established in 1863 by the First Oregon Volunteers, however historic documents establishes Camp Logan on Sept. 16, 1865, by Captain A. B. Ingram, one officer and 40 enlisted men of Company K, First Oregon Infantry volunteers.

In 1867, Captain Marcus Reno, who later fought at Little Big Horn, described Camp Logan as “situated in a beautiful and extensive valley called Strawberry Valley on a creek of the same name and a tributary of the John Day’s River.” It is approximately six miles south of Prairie City, at the base of Logan Butte, or Strawberry Mountain as it is known today. Strawberry Creek runs through what was once the site of the camp, although in 1865 the creek was known as Indian Creek and later Logan Creek.

After the Civil War, Camp Logan was manned by the 1st and 8th US Calvary, with other regiments on attached service. Many of the soldiers at the camp were veterans of the Civil War and had received honors for meritorious service. The purpose of the camp was to protect the settlers in the Upper John Day Valley from the “depredations” of the Indians. It was named Camp Logan in memory of William Logan, formerly a United States Indian Agent at Warm Springs Indian Reservation in the 1860s.

Camp Logan was advantageously located, and guarded the best Indian passes, in the John Day Valley. Had the camp been continuously and properly garrisoned the valley’s settlers and travelers on the Boise to The Dalles road would have been better protected.

However, in May 1866 the soldiers were withdrawn to nearby Camp Watson, about 70 miles away, near present day Antone. This was an unfortunate time for the camp to be abandoned. During that summer, a band of about 50 Indians raided the Elk Creek and Dixie Creek regions, murdering, burning buildings and stealing stock. Business was at a stand-still. Camp Watson was too far away to be relied upon for help and so the country was left practically unprotected. Finally due to the successful petition of the citizens of Grant County, Camp Logan was again reoccupied on Dec. 6, 1866, by Lieutenant Charles B. Western of the 14th Infantry and 45 men of Company F, 8th Cavalry. Believing that the Indian problem was solved, the camp was finally evacuated in 1869.

Prior to 1867, there were only a few log buildings and the men were living in tents. When Brevet Colonel Marcus Reno inspected the camp he found the camp “in wretched condition, and much discontent among the men.” Many desertions had been reported and the camp was poorly supplied. Reno held Capt. Dudley Seward responsible. He felt the commander was “too indulgent.” He also noted a lack of record keeping, perhaps some mismanagement of funds, poorly uniformed soldiers and a lack of training. During his inspection the camp was in the process of building quarters and other outbuildings.

Capt. Seward wrote a letter to the Department of the Columbia about one month after the inspection and reported things greatly improved. The camp now had a company quarters, storehouse, blacksmith, hospital, stable, shed for mules, bake oven and a cookhouse with adjoining mess room. These buildings were built of hewn logs, with shake roofs. There were also two officers quarters, one conveniently located over a spring. Later, a cemetery was located next to the camp that interred two to three military men, although only one death has been documented. The camp usually garrisoned 100-200 men and about as many horses and mules. In 1867 the camp listed 18 teams, 44 pack mules and three wagons.

Although the soldiers did not participate in any major battles their dedication and heroics were no less important. Unlike their experiences in the Civil War, they were fighting a skilled and often unseen foe in a hostile environment. The soldiers would often travel as far as the Steins or over the Blues to the Malheur. In the winter, “icicles would form upon their moustaches about an inch in length every hour.”

They were poorly paid, and poorly supplied. As at all western outposts, desertions ran high. At least one soldier had been killed and many others wounded.

After Camp Logan was closed many of the soldiers went on to gain notoriety in other Indian battles in Oregon and the West.

Dianne Lesniak of Prairie City is a fifth-grade teacher at Prairie City School. She also is a Camp Logan historian and member of the Prairie City History Club.