State board takes pulse of forests

Published 4:00 pm Tuesday, November 25, 2008

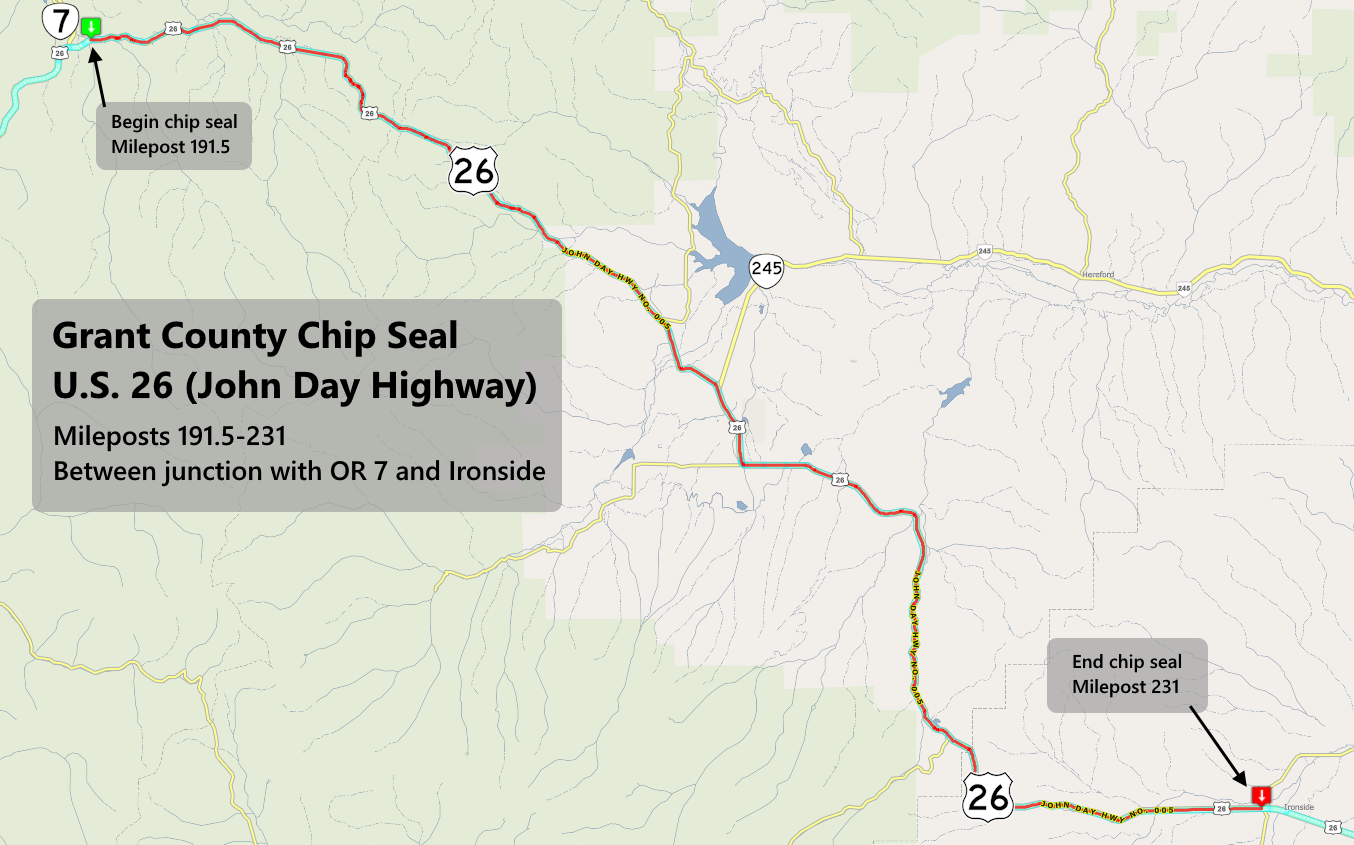

- <I>Contributed photo</I><BR>Ed Clark, Blue Mountain Ranger District fuels planner, talks with local forest officials, citizens and State Board of Forestry members on a tour of Malheur National Forest sites last week. Below: Dave Traylor makes a point during the public comment period of the meeting.

JOHN DAY – The Oregon Board of Forestry got some frank assessments of collaboration, the latest wrinkle in forest project planning, at a meeting last week in John Day.

The comments ranged from “woefully slow” to “the only hope” for restoring forest health, keeping mills operating and saving rural communities.

“We desperately need industry to be retained in this valley,” said John Shelk of the Ochoco Lumber and Malheur Lumber companies. “Ultimately, it comes down to collaboration.”

However, he also acknowledged that collaboration – a process in which environmental, industry and community advocates hash out their differences on forest projects – is cumbersome and time-consuming.

“And it doesn’t currently produce the outputs that our company needs to survive,” Shelk said.

The Forestry Board traveled to John Day last Friday, Nov. 21, to tour several U.S. Forest Service project sites and discuss forest health with local experts. The session drew about 60 people to a meeting room at the Malheur National Forest headquarters.

The board is considering a report from the Oregon Department of Forestry’s Federal Forestlands Advisory Committee regarding the 58 percent of Oregon forestlands that are federally managed.

The committee’s draft details a vision, goals, challenges and actions for those forests, and it emphasizes the interconnected nature of state, federal and private forest lands.

“Across Oregon’s forested landscape … federal forestlands should help deliver a set of environmental, economic and social benefits sufficient to ensure that the State’s forest resource in total is sustainable,” the report states.

The report also notes a “sense of urgency” as the federal forests become increasingly overstocked and unhealthy, leaving them vulnerable to catastrophic wildfire and insect damage. At the same time, the state report notes that the infrastructure – the mills and logging industry – needed to clean up the forests is rapidly disappearing, particularly in Eastern Oregon.

A local panel urged the ODF Board to push ahead with the report’s recommendations, including creation of a federal forestland liaison program to work with local communities and federal forest managers. In addition to Shelk, the panel included Boyd Britton, Grant County commissioner; Tim Lillebo of the conservation group Oregon Wild, and Diane Vosick of the Nature Conservancy.

Panelists called for better funding of the U.S. Forest Service to move sales off the drawing boards. They also asked for the ODF’s technical assistance in preparing sales.

Boyd Britton praised the state forestry agency, referring to its credibility among resources agencies operating in the state. He urged the board to “use that bully pulpit” in the political arena to take action for forest health and survival of mills and communities.

He noted that negotiations last spring produced sales in the Thorn and Egley fire salvage areas and also got another project, the Crawford sale, out of a limbo created by appeals and changing conditions. The Crawford sale had been on the books for 12 years, he noted.

“We’ve got to do better than 12 years,” he said. “And politics is what moves things ahead.”

Speakers also lamented the relatively small size of projects that get done through today’s collaborative process.

Board member Barbara Craig expressed concern that “we’re not getting the scale needed” – and asked if we’re making deals on a “micro level” because of concern because people can’t agree on a larger landscape.

Several local speakers agreed with that assessment and said progress often hinges on the buy-in by a few dissenters. Britton said the process doesn’t give enough deference to the abilities of trained federal and state land managers.

“If we’re just going to second-guess them, let’s fire them,” he quipped. “These folks know how to do it. Mr. Shelk knows how to do it.”

Shelk said he’d rather see collaborative efforts move faster, but he also called collaboration “the only game in town.”

He noted the transformation of the eastside forests over the past 25 years, from “an absolute timber orientation” to a near shutdown of logging in recent years. The Malheur National Forest was selling about 250-280 million board feet a year in the early 1980s, he said. Today, the cut is closer to 10-15 million board feet, and it has dipped to zero in recent years.

Shelk said environmental litigation had forced land managers to change their strategy to try to make timber sales survive appeals and lawsuits. That didn’t work, however, and it got to where his company “didn’t purchase a federal timber sale for 10 years on the Malheur,” relying instead on other timberlands.

Now, he said, the hope is that through collaboration, the parties can build trust and reverse the process that essentially halted the timber program on the MNF.

Lillebo of Oregon Wild agrees that the science today supports active management for a functioning ecosystem.

“I believe there are hundreds of thousands of acres out there that could use active restoration management,” he said.

While an advocate of protecting old growth, he conceded that Oregon’s forests are overly dense, making them more susceptible to fires and insect infestation. He thinks the conservationists, communities and industry can “find common ground” to manage the forests.

“The way to do that is through collaborative groups,” he said. conceding “It’s a lot of damned work, and it’s not always fun.”

Others aren’t so sure about the prospects for collaboration.

“Is it working?” Harney County Judge Steve Grasty said about collaborative efforts. “The pessimist in me says it’s not … Environmentally, we’ve got a disaster out there.”

Grasty said the continuing deterioration of the federal forests in this region also is taking a toll on the social and economic fabric of the region. Communities need jobs or “we will go away,” and the timber industry needs a predictable supply of timber to keep mills going and do forest preservation work.

He echoed an earlier statement by Diane Vosick of the Nature Conservancy: “There’s a need to treat.”

Grasty said Harney County will push ahead with collaborative efforts, although others in the audience were clearly frustrated.

Dave Traylor, representing the Grant County Public Forest Commission, said he’s tired of the “my way or the highway” tenor of some discussions on forest projects.

“Time is critical,” he said. “We need to protect this infrastructure, but we don’t have time. We’re sinking.”

He said that for collaboration to work, there needs to be a specific goal, a time limit on the debate, and some level of consensus at the end.

Ted Ferrioli, the state senator from John Day and also with Malheur Timber Operators, worries that collaboration is really just setting the resource communities up for “a better form of failure.”

The current process defers to individuals who are the most litigious, he said, delaying solutions in the quest to appease the dissenters.

“Don’t oversell collaboration,” he warned.

He also urged the board to help inform people about the dire state of Oregon’s federal forests.

“Oregon’s forests are burning up, rotting and dying, and getting fed to the bugs,” he said.

Research indicates, he added, that “within the next three decades, this forest, the Wallowa-Whitman and the Umatilla, will burn.”

He urged the board to help get that message across to the rest of the state.

“I would ask the board to help define the problem and set the clock,” he said. “We don’t have decades to resolve these issues.”

Chuck Burley of the American Forest Resource Council warned against seeking collaboration on every project – “collaboration for the sake of collaboration.”

He said it just doesn’t work in some situations, and it results in delays because it doesn’t replace environmental assessment processes required for many forest projects.

An enviromental impact statement can take 18 months to complete, he noted, and collaborative processes add on to that time table.

Participants in the discussion last week pointed out that the Blue Mountains Forest Partners have been meeting for almost two years on the Dads Creek project, northeast of Prairie City.