Decriminalizing drugs: Measure 110 affects possession of small amounts

Published 12:04 pm Tuesday, December 15, 2020

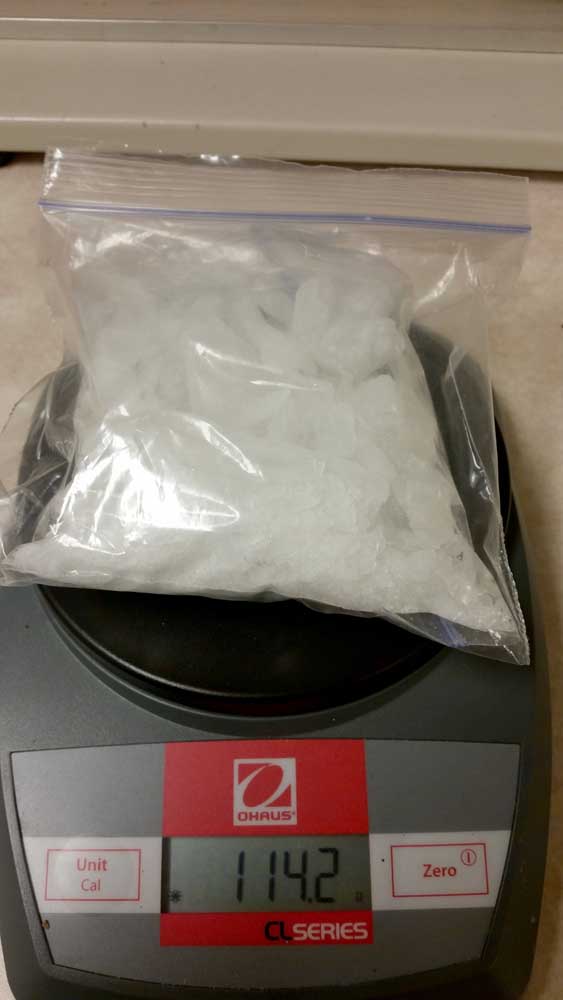

- About 4.3 ounces of methamphetamine, along with drug paraphernalia, was discovered during a warrant search of a silver Dodge Stratus stopped on Highway 395 north of Mt. Vernon April 16, according to Oregon State Police.

Changes are coming to Oregon’s drug laws after state voters decriminalized possession of small amounts with the approval of Measure 110 in November.

Although the law takes effect Feb. 1, 2021, Grant County District Attorney Jim Carpenter said in a press release his office would begin resolving cases with the new metrics in mind.

Carpenter said pending cases that would fall under Measure 110 would be made “a violation offer with a referral to a local drug treatment program.” Incoming cases will be charged as violations as they would be under the new law, and pending and incoming cases that involve a mix of charges with some that would fall under Measure 110 will be charged and resolved “according to the applicable law at the time of the offense,” he said.

State Rep. Mark Owens, R-Crane, said he is working with the Legislative Council to draft a proposal to take to the legislative session that would allow districts to opt out of the measure to allow drugs to remain a crime.

“I believe that mental health and addiction is an issue,” Owens said. “There needs to be a repercussion for actions, and we’ve taken all repercussions for actions out.”

Owens said the state could do more to treat addiction, but he said people in his district want drug possession to remain a crime.

“We’ve allowed hard drugs to be acceptable in the view of our children by passing this bill, and that is wrong,” Owens said.

State Sen. Lynn Findley, R-Vale, said he liked some components of the law, but he is not for decriminalizing drugs.

He said counties should have “local control” rather than a “one-size-fits-all” approach.

Findley said there have been discussions about taking the approach lawmakers used in 2014 when Measure 94 passed. Counties and municipalities that voted against the initiative were given the option to ban production and sale of marijuana locally.

He said it took 18 months for the Legislature to pass laws making Measure 94 work as intended. Measure 110, he said, is as complex.

“It’s going to take a while to get there,” he said.

Measure 110 and what it does

In November, Oregon voters passed Measure 110 by a 59% margin. The initiative is the first of its kind in the United States.

Grant County voters overwhelmingly turned down the Measure, with 2,811 opposed to 1,626 in favor.

The law ends criminal penalties for user amounts of drugs, including heroin, methamphetamine, LSD and ecstasy, which will be punishable by a $100 fine that can be waived instead for a health evaluation.

The bill’s text also reduces penalties for non-commercial felony drug possession cases involving larger quantities.

Before, user amounts of drugs were misdemeanor crimes punishable by a maximum of one year in jail and a fine of up to $6,250. Now, it will be classified as a violation like a traffic ticket.

The measure requires new “addiction recovery centers” be set up around the state, with at least one in the service area for each existing Coordinated Care Organization.

In the text of Measure 110, ARCs provide the following: triage, health assessments, referrals, peer support and outreach.

However, in an opinion piece in The Oregonian, Heather Jefferis, executive director of the Oregon Council for Behavioral Health, and Se-ah-dom Edmo, co-chair of the Oregon Recovers advocacy group, said the measure removes a pathway to addiction treatment as it relates to diversion programs.

They said a teenager could get caught with a user amount of drugs and only have to pay a fine and would be able to hide it from their parents.

Many people struggle to get clean, they said: If they could do it on their own, they would not be addicted.

According to an implementation schedule, the measure will issue grants for treatment providers to expand treatment services, but there’s no budget set. That money comes out of the marijuana tax fund currently being used for schools and other health programs.

A counselor’s perspective

Thad Labhart, Community Counseling Solutions’ clinical director, said the measure will pull funding from existing community-based treatment programs and allocate it to the ARCs. Labhart said it has its “pros and cons.”

He said CCS does not take a position on the initiative.

Labhart said so far he is “somewhere in the middle” and much has to be determined on the state level to implement the measure.

“The upside is it puts focus more on treatment, which I think, in many situations, has an upside for low-level offenses,” he said. “The downside is that it removes funding from pretty substantial influential existing programming and moves it to an unknown.”

Law enforcement outlook

In November, Grant County voters overwhelmingly turned down Measure 110 and overwhelmingly elected Community Corrections Director Todd McKinley to head up the Sheriff’s Office.

McKinley said he fears the measure will backfire and lead to an increase in an already significant methamphetamine problem.

“The other side of this is typically what we see,” he said. “They commit crimes to obtain things to sell to buy their meth.”

He said when someone is issued a violation for user amounts of drugs, in the long run, it will extend the time it takes to get them through the system.

He said law enforcement agencies will lack the ability to get users into treatment through diversion programs tied to arrests.

McKinley said the ballot measure was “misleading” in how it was written, in that it did not take into account the shortage of beds at treatment facilities in the state.

“We have a difficult time getting the current patient load that we have in to inpatient treatment around the state and finding a bed available,” he said. “I don’t know how it’s going to work with the numbers that I think they’re going to expect to be pushed that direction.”

A Criminal Justice Commission report found that there are roughly 200 residential treatment beds in Grant County’s CCO, which it shares with 11 other counties.

From criminalization to treatment and recovery

According to the Drug Policy Alliance, the nonprofit group that backed the measure, 9,000 people a year are arrested in cases where misdemeanor drug possession is the most severe offense.

According to Drug Policy Alliance, low-level offenses have long-term consequences on employment, education and housing. Typically, people become entangled in the criminal justice system, unable to get a job, violate their probation and end up back in jail.

Susan Church, the vice chair of the Democratic party in Grant County who supported the initiative, said she was not immediately sold on the idea of decriminalizing low-level offenses.

“When I first looked at it, my immediate reaction was, ‘Oh, that’s not going to work,’” she said. “Then I looked and did some research on it, not just reading the measure itself.”

Church said she believes people would recognize decriminalization is not a “free pass” and the treatment-focused approach will address the drug problem in the community.

Labhart said he appreciates people’s concerns about decriminalization and points to the research as well.

“A lot of people want to see folks locked up, and I very much appreciate it,” he said. “But again, from a treatment perspective, it’s been shown to work better than incarceration for low-level drug (offenses) as far as recidivism.”

Effective Feb. 1, possession of Schedule 1, 2 or 3 controlled substances is a class E violation, unless the possession is part of a commercial drug offense.

Possession of a controlled substance remains a misdemeanor with:

• 40 tabs or more of LSD

• 12 grams or more of psilocybin

• 40 pills or more of oxycodone

• one gram or more of heroin

• one gram, or five pills, or more of MDMA

• two grams or more of cocaine

• two grams or more of methamphetamine