Scholars shine new light on Black pioneer family in Grant County

Published 9:44 am Monday, September 30, 2024

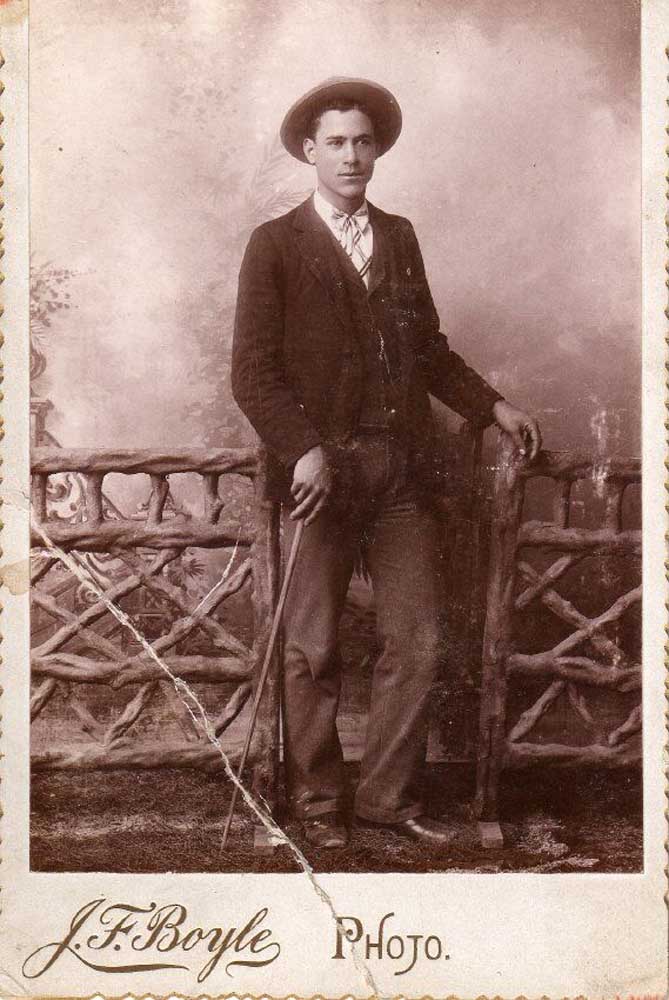

- Joe Sewell

CANYON CITY — Recent scholarship has shed new light on the exploits of Columbus Sewell and his family, who found a home in Canyon City at a time when Blacks were legally barred from living in Oregon.

Trending

According to Zachary Stocks, executive director of Oregon Black Pioneers, Columbus Sewell and his kin were the first Black family to settle in the state east of the Cascades and became prominent and successful members of the community.

Stocks shared fresh insights into the lives of the Sewells during a public talk sponsored by the Grant County Oregon Historical Association before about 40 people at the Canyon City Community Hall on Sept. 23.

Details about some aspects of the life and times of the Sewell family that have been muddled due to the passage of time were given some clarity by Stocks, specifically the way in which hard-riding and hard-fighting Joe Sewell met his untimely end.

Trending

Attendees were first treated to a short film produced by Oregon Black Pioneers in collaboration with the High Desert Museum and North East Production called “Meeting the Sewells,” which sees Stocks transported back in time to the Sewell residence in Canyon City in 1890 after donning an old bowler hat.

Along with covering the history of the Sewells, Stocks touched on the struggles Blacks faced while attempting to make a life for themselves during Oregon’s infancy. The Sewell family, like many other Blacks in rural Oregon, were more readily welcomed and accepted by their white neighbors than those who lived in the state’s urban centers.

The Sewells of Canyon City

Stocks said Columbus Sewell was born sometime between 1820 and 1823 in Washington, D.C. The identity of Sewell’s father is unknown, but he was listed as a mulatto in censuses taken in 1850 and 1860.

Family sources suggest Sewell came out West to try his hand at being a white man.

His first foray into the frontier was to Mineral Point, Wisconsin, where he reportedly served in the Black Hawk War. Stocks suggested the story of Sewell fighting in that war was likely an embellishment — Sewell would still have been a young boy during the war, which began and ended in 1832.

Sewell would later left Wisconsin for California following the discovery of gold in 1849, staying there until as late as 1861.

By 1862 Sewell made his way to Canyon City with Bradford Trowbridge due to the discovery of gold in the area, which led to an influx of over 10,000 people.

Trowbridge would ultimately build the first ranch in Grant County, and there is speculation Sewell may have helped in its construction. A road connecting Canyon City and The Dalles was completed in 1864, leading to both Trowbridge and Sewell starting freight hauling businesses shortly afterward.

Sewell operated a single wagon with 12 horses during his time running freight between Canyon City and The Dalles, a round-trip journey that took six weeks in the 1860s.

Sewell married a woman from Richmond, Virginia, named Louisa who was born into slavery and was over 20 years his junior. Not much is known about her early life.

The pair had three children, with sons Joe and Tom surviving into adulthood. Known for her ice cream and for the croquet court constructed opposite the Sewell home, Louisa would pass away in February of 1893.

Tom was born on June 4, 1869, and he would go on to become a well-respected and well-liked member of the community. Like his father, Tom worked at the Trowbridge Ranch for a time before getting into the freight business himself.

At one point, Tom was incarcerated at the Oregon State Penitentiary for the crime of selling alcohol to a Native American during the Prohibition era. A petition for leniency was circulated throughout Canyon City and signed by most of the men in town.

A rebuttal was written by Grant County Judge J.H. Allen to the federal judge presiding over Tom Sewell’s case, urging that he be punished severely. The rebuttal appears to have been successful as Tom was not granted leniency and served the full term of his sentence.

Tom was married twice, first to a woman named Cora on Nov. 2, 1899. Cora would pass away on Nov. 2, 1919, and Tom would later relocate to Portland and marry a woman he met there.

Tom’s second wife, Sadie, remained in Portland while Tom returned to Grant County with a housekeeper named Julie Jackson following the marriage. In 1943, following the death of Jackson, Tom retuned to Portland, where he sustained a head injury.

Tom would ultimately succumb to that injury, passing away just a few days later. Following his death, Tom’s wife brought his body back to Grant County to be buried in the Canyon City Cemetery along with the rest of his family.

The younger Sewell son, Joe, was born on April 11, 1872, and was widely known as an athlete and pugilist during his day.

“A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788-1940” by Elizabeth McLagan describes Joseph as “an attractive rogue and an excellent horseman and athlete, addicted to the wild and woolly aspects of frontier life, where drinking, racing and fighting were daily events.”

The work also describes Joe as the best fighter in the area for a time during his childhood, noting that he took on all challengers. Joe Sewell met his unfortunate end on May 10, 1898, less than a month after his 20th birthday.

There were two separate accounts of how Joe met his end, neither of which was accurate, according to Stocks. Joe Sewell ultimately died in an attempted murder-suicide involving a prostitute from Pendleton.

Joe had been dating the woman for some time and wanted her to meet the rest of his family in Canyon City. There was just one problem, however — Joe had never told the woman that he and his entire family were Black.

Horrified at the discovery, the woman decided she wanted nothing more to do with Joe. Joe would later shoot his old flame before turning the gun on himself.

The woman in question would survive the ordeal, while Joe would not.

Columbus Sewell passed away on Jan. 17, 1899, in Canyon City, according to an obituary published in The Oregonian on Jan. 23 of that year. The obituary described Sewell’s career as a resident in the community as above reproach.

“Every act of his life was based upon moral law and in no instance was he ever accused of unfairness (or) unjust dealings,” the obituary read. “Not a stigma rests upon his good name and he has passed to his eternal home honored by all who knew him.”

Sewell legacy

Stocks described the legacy of the Sewell family as one of perseverance and risk-taking.

Only 3% of those who headed out West in search of a better life were Black. The number of Black pioneers in Oregon was around 200 at that time, according to Stocks.

Oregon’s exclusion laws, the first of which was passed in 1844, prohibited Blacks from settling, owning property, making contracts, voting or using the legal system in the state. Those laws were superseded by the 14th Amendment to the Constitution but wouldn’t be repealed by Oregon voters until 1926.

Blacks were also left out of the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850, which offered 320 acres to each unmarried male citizen and 640 acres to each married couple. Claimants simply had to live on and make improvements to the land for four years — but the law only applied to whites or people of mixed white and Indian ancestry.

The discovery of gold led to a rush of Black settlers and miners into Oregon, however.

The Homestead Act of 1862 made free land available to Americans regardless of race, and the end of the Civil War led to an increase of Black settlers coming into Oregon. In fact, Blacks came to Oregon at higher rates than whites between 1868 and 1871.

The Sewells overcame all of the obstacles set before them, becoming one of a handful of Black families to have a successful homesteading claim.

Columbus Sewell’s homestead would remain with the Sewell family until its sale in 1921.

The Sewells challenged Oregon’s exclusion laws and saw increased opportunities for Blacks within their lifetimes.

Those increased opportunities can be measured through the Sewell family, who arrived in Oregon when Blacks were banned from living and conducting business in the state yet went on to establish successful freight businesses and become beloved members of the Canyon City community.